The data, the hypermedia and the documentation

By Arnaud Lauret, April 24, 2015

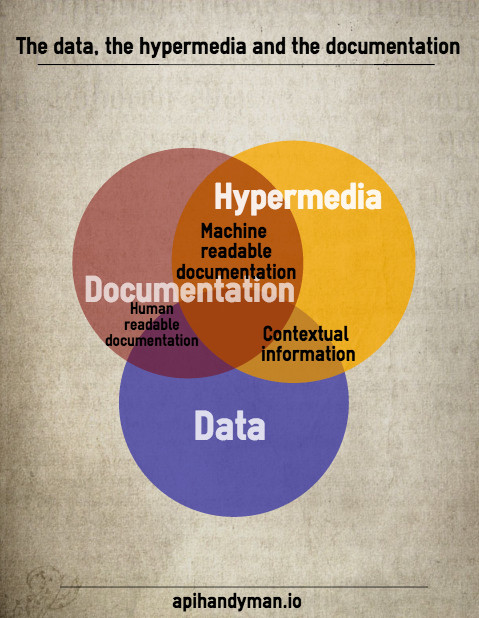

When I look at hypermedia media-types and API definition languages I feel that the frontier between data and documentation is becoming thinner as my knowledge of the API world grows and as the API world evolves.

Some complain that hypermedia APIs are overloaded with useless, redundant, ugly, complex, … data and/or tend to be hardly readable and/or are inefficient in environments where 1 byte is what separates total failure from awesome success (have you ever feared the E icon on your smartphone when using an app relying on data?) .

Others complain that some APIs are not developer/consumer friendly and it’s boring, hard, painful, … to find , when needed, the accurate documentation or information, wether it’s machine or human readable (have you ever feared the enigmatic 1138 error and we will not tell you more message or the cryptic understandableButEnigmaticName field while using an API?).

The API inquisition may find all this a bit exaggerated and put you on trial for even thinking about these heretic opinions, but we can’t deny there’s some truth in that.

REST is defined by four interface constraints: identification of resources; manipulation of resources through representations; self-descriptive messages; and, hypermedia as the engine of application state.

[…] the messages are self-descriptive and their semantics are visible to intermediaries.

Roy Fielding, Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures

When I read that, I understand message = data + hypermedia + documentation but I’ve no clue about what it means concerning the organization of the message.

Documentation is data. Hypermedia is data. All is data.

My new motto.

Let’s see how data, documentation and hypermedia are intertwined in REST APIs, I sense there’s something to dig in there…

API documentation

In the API world there are two types of API:

- The good ones: those which have a documentation

- The bad ones: those which don’t

In the good API world there are two types of documentations:

- Machine readable documentation

- Human readable documentation

Machine readable documentation

Nowadays, talking about machine readable API documentation, is talking about API definition language.

This post is not intended to be a detailed description and comparison of API definition languages. For more information you may take a look at these Mike Stowe’s and Kin Lane’s posts.

The most known are RAML, Swagger and Blueprint. These API definition languages allow you to define and describe:

- Endpoints

- HTTP verbs you can use on endpoints

- Input needed when calling an endpoint with a specific HTTP verb

- Output returned when calling an endpoint with a specific HTTP verb

- Error handling

- Data models used on input and output (to avoid defining multiple times the same resource)

- Security

- Media-types awaited and returned

None of them, for now, handles hypermedia APIs definition.

By the way, actually many people (like myself some time ago) think that Swagger UI (or equivalent) aka The Swagger is an end in itself, but it’s only a representation of an API’s Swagger definition. You can use API definitions to generate SDK, mocks, server stubs, Postman collections or whatever you wish related to your API’s definition.

You may also have heard about another thing called ALPS.

Not Alps, the european mountain range, but ALPS, the Application-Level Profile Semantics created by Mike Amundsen, Leonard Richardson and Mark Foster.

ALPS describes the operations (actions) and data elements of a service. that’s all. that description is the same no matter the designtime tooling, protocol, or message format used. that description is the same whether you are implementing code on the client-side or server-side.

Kin Lane, What is ALPS

To be frank, I have not yet fully grasp ALPS, how it differs from RAML, Swagger and Blueprint and all its implications. I’ll have to dig into the IETF draft, discuss with smart people, test via my API crash test and write some post(s) about this.

But, for now, I understand that ALPS allows you to describe your data and what you can do with them.

It can be used as source material to generate:

- Swagger, RAML or Blueprint API definition

- Simple CRUD service

- The hypermedia meta-data for your hypermedia API

I also understand that using ALPS to describe a service, even as a simple specification/contract, on each level (client/server) you ensure that implementation are sharing the same “vision” of the limits of the service.

To learn more about ALPS you can read this introduction by Kin Lane and the IETF draft.

Putting all these machine readable documentations together we’re able to define and describe:

- Data and relations between data

- Possible actions on these data

- What we need to do these actions

- What we get in return

- How errors are handled

- How consumer and provider could talk to each other (security, data format)

Of course nowadays not every API in the world offers this level of completeness in machine readable documentation. And even if this level is reached, there are always a few things, that do not fit in this kind of documentation, to explain to poor humans who have to use your API.

Human readable documentation

Human readable documentation takes roughly three forms:

- Pretty machine readable documention

- Novel documentation

- Dark documentation

Pretty machine readable documentation

Machine readable documentation is written by humans and therefore is readable by humans (but not all of them).

This kind of documentation can be displayed in a more accessible and visually appealing way with tools like Swagger UI for example.

This kind of documentation is not only pretty it’s also smart, it offers users a way of testing the API within its documentation.

Novel documentation

API’s definition is only the Alpha of documentation.

The Omega is every single thing you think to explain and that do not fit in API’s definition:

- How to connect using Oauth 3.2b3

- Throttling limitations (3,5 calls every 56 seconds for bronze users)

- How the Cobol/Pascal/Basic sdk works on an Apple ][

- …

You explain these things by writting (ed. and drawing!) plain good old documentation with text, snippets, diagrams… You provide it to users in HTML, PDF, markdown, printed books with rich illuminations or even engraved stones (for gold users only).

You can also use tools like API notebook to make this documentation more interactive.

Dark documentation

Dark documentation (in reference to dark matter) is all that’s between the Alpha (pretty machine readable documentation) and the Omega (novel documentation).

It’s all the piece of informations we can find in the API designers and developers brains, by contacting the support, searching stackoverflow, reading blog posts or forums.

Data and Hypermedia media-types vs documentation

After documentation comes implementation, what do we get with our data in API’s message? Many things.

A good practice when handling error with your API is to give a link pointing to documentation concerning the error (human readable documentation). Some APIs, like PayPal’s, allow developers to choose the level of information they get when there’s an error.

When you add the hypermedia dimension (ed. sounds like a sci-fi book or movie title) to your API, you add data that define and describe:

- Data and relations between data

- Possible actions on these data

- What we need to do these actions

- What we get in return

- How errors are handled

All of this sounds familiar, no? It looks like a lot of what we have with machine readable documentation and a bit a human readable documentation!

But there’s more. If documentation describes what could be, hypermedia describes what is. Hypermedia gives you informations based on the context:

- The actions that are actually possible in the context

- Prefilled links with ids and parameters (or templates to build this links)

- Prefilled value for actions

What I see now is that most of hypermedia data comes from the documentation and even part of the informations based on context could come from the documentation.

What else?

Here comes the true purpose of this post.

The web browsing analogy

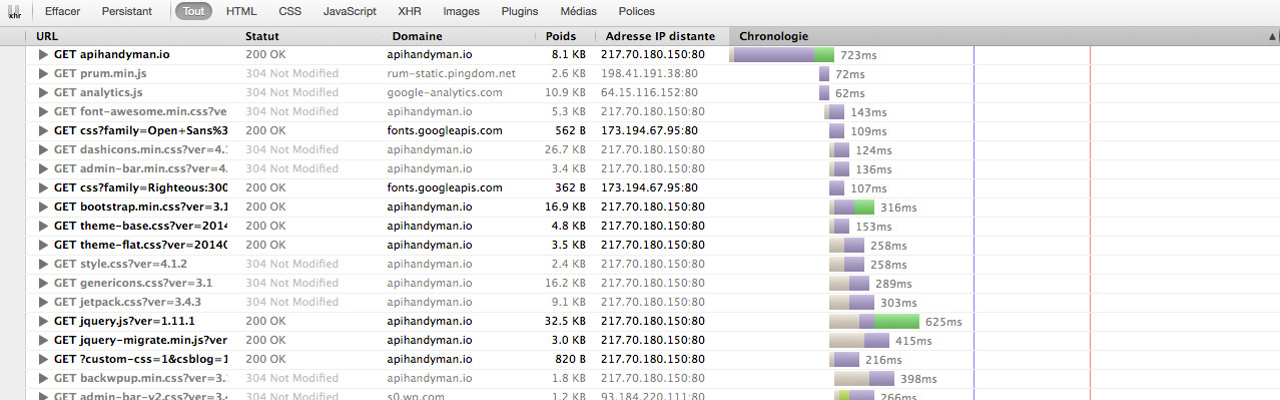

When you browse a website:

- Your web client first loads an HTML file /persons/1234/items.html

- Then it loads all resources (css, js, images) referenced by this file

- It can therefore present you a rendering of all these elements

- If you click on a link, the browser loads another HTML file /persons/1235/items.html

- But, then it will only load new or modified referenced resources

- It can therefore present you faster and with less data a rendering of all these elements

When you build a website:

- If you want, you could choose to only load the HTML and read it

- If you use tools like Firebug you can actually have a complete vision of HTML, css, js and other resources in one place

Why couldn’t we do all that with hypermedia APIs?

Browsing hypermedia APIs

We could apply a separation between concepts when browsing a hypermedia API like we do with HTML:

- Your API client first load some data GET /persons/1234/items

- Within these data (or in headers) you have a (or some) reference(s) to the machine and human readable documentation

- It can therefore build a complete message including all data, hypermedia and documentation

- If you make another call GET /persons/1235/items

- Within these data (or in headers)

- The API client can build a consolidated message including all data, hypermedia and documentation faster as all redundant data has already been loaded

Let’s push the enveloppe on this, we could also imagine to modulate the level of enhancement we apply to the data, we could:

- have the data alone

- add linked resources to hypermedia data

- add linked resources to human readable documentation

- embed hypermedia data

- embed human readable documentation

You may ask: but why would we do all that? We would do that to propose the necessary level of information depending on the context:

- A developer wants to discover the API? Let’s put all we have and present it via the ultimate API playground: a hypermedia API browser able to present all these informations (data, hypermedia, human readable documentation) in a cool way

- After playing with the API, the developer starts to build an application to consume it. Let’s give then data + hypermedia data + a part of documentation (detailed errors for example)

- The application goes on the App Store, we juste give then data + hypermedia

- We could also send data only (don’t know why… but why not)

To be continued

This ideal is not yet real but as things evolves around hypermedia APIs I think we could see quickly arisen the tools which will help to create this ideal. Stay tuned, I’ll be back with other posts about this.

PS: I had the pleasure to finish this post after #apisberlin birds of a feather where I had the opportunity to talk about this subject with other API nerds. That was great to talk hypermedia with you guys!