Building a healthy and profitable relationship between tools and specifications

By Arnaud Lauret, March 9, 2022

We may never have a clear answer to the question “what comes first? Tools or Specifications?”. What is sure is people create tools or specifications based on their needs. Those tools and specifications, like OpenAPI, AsyncAPI, or JSON Schema, are tightly intricated. What could be done to build a healthy and profitable relationship?

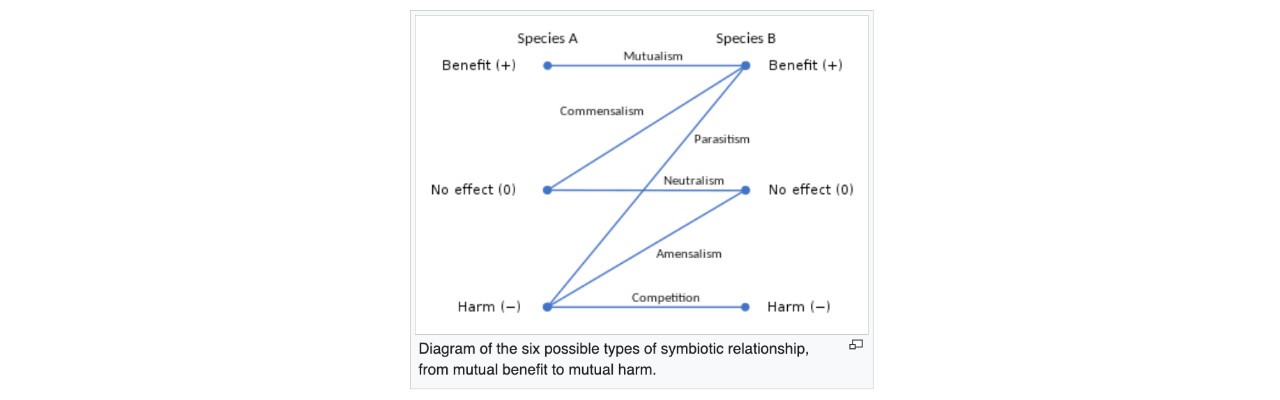

This post’s banner is a diagram of the six possible types of symbiotic relationship, from mutual benefit to mutual harm. Symbiosis (from Greek , symbíōsis, “living together”, from , sýn, “together”, and , bíōsis, “living”) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic. The organisms, each termed a symbiont, must be of different species. Source Symbiosis - Wikipedia

Special thanks to Bruno Pedro for raising the “who’s first” question while I was tweeting on that “no tools, no standard/specification” topic.

Why do specifications need tools and reverse?

Let’s take an example. I could talk about the OpenAPI Specification but to change I’ll talk about JSON Schema (which is actually used by OpenAPI).

JSON Schema aims to describe formally your data formats. For instance, if I build a command-line tool that needs a configuration file. I can define its structure using a JSON Schema without writing a single line of my application code (I’m in the design first/spec first team!).

{

"$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/schema",

"title": "SuperCliConfiguration",

"required": [

"sourceRepository"

],

"properties": {

"sourceRepository": {

"type": "string",

"pattern": "^https?://.*.git$"

}

}

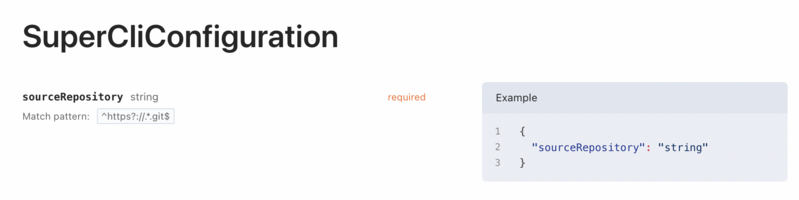

}The JSON Schema specification is human-readable and as an (experienced) human being, I can see that, in the “SuperCliConfiguration” schema, the property “sourceRepository” is required and it must be a URL ending with “.git”.

But not all human beings can read such a format easily, especially when it describes complex schemas. And not all of them are happy reading JSON. So it is nicer to show them a rendering that is more accessible.

Such documentation tool taking advantage of JSON Schema is great in itself, that enhances my tool’s documentation. But it would be a pity to confine this format to documentation.

Such a specification document is interestingly used in code. I can use this schema with the ajv library to check that a configuration file is valid without writing much code.

And that’s not all, the schema I have created is not only interesting for me. If someone else wants to build a tool that generates my tool’s configuration file based on some data they have, they can take advantage of my JSON Schema to do so.

A specification without tools will never be used widely and will probably disappear quickly. Indeed, without tools taking advantage of it, what’s the point of a specification? It’s like writing a musical score and never playing it.

The tools specifications relationship is not a one-way one. People creating tools can avoid losing time reinventing the wheel by taking advantage of specifications.

And even more important, tools enhance their interoperability by using specifications. They share a kind of “standard” (not all specifications are strictly standard anointed by some standard organization) easing communication with other tools (in a broad sense, it’s not only about APIs). And, icing on the cake, those interoperable tools using specifications become part of a greater whole, enhancing their visibility, letting them participate in various ecosystems.

So, no specifications without tools. And “not no tools without specifications”, but better tools with specifications. But what can be done on both sides to ensure a healthy relationship profitable to everyone involved?

Tools perspective

As someone involved in the creation of a tool that could take advantage of a specification, I would expect the following when looking for information about a specification:

- A clean short description of what the specification does, what problems it is trying to solve

- A few use cases examples that show me how the specification could be or actually is used in the real world, accompanied by short code samples

- An exhaustive list of complete use cases, explaining everything in details

- An exhaustive, example-based, description of every element of the specification

- Some reference implementations

- Obviously the technical documentation à la RFC (for the purists)

I also hope any fashion of presenting information and teaching to be used. I expect not only text but also figures, interactive diagrams, tutorials, videos, ready-to-use git repositories, … In my wildest dreams, I would love to see also training and certifications.

If you’ve read me or seen me talking about API DX (Developer eXperience) and documentation, what is described above should sound vaguely familiar. With modern web APIs, we’ve been used to be able to understand and use an API in no time, easily. Being provided with information and helper material/tools in many forms. That should be the same for anything, and specifications are no exception.

Not taking care of the IX, Implementer eXperience may seriously hinder a specification adoption. It may also lead to incomplete and even invalid implementation, hindering, even more, the specification adoption.

Specification perspective

As someone who is involved in the creation of a specification or as a user of the tool taking advantage of a specification, I expect the following from implementers:

- Explain from a high perspective why the spec is used in the tool

- Explicitly state which version(s) of the specification is (are) supported

- Explicitly state which portion/feature/part of the spec is supported and for what purpose

- Explicitly state which portion/feature/part of the spec is not supported (and possibly why)

- Provide a roadmap of specification support (for instance, for OpenAPI, knowing if 3.0 and 3.1 support is planned and for when is welcomed)

People creating specs AND tools’ users need to know how specifications are actually used.

Regarding specification creators, some could object “why would I do extra work for them”. Well, “they” work hard on defining a specification for the community, so be nice to them, what they do is good for you remember? Your tool becomes part of a huge ecosystem thanks to their work (and yours actually). Not that means specifications creators should provide a standard way of stating what is used on how (and possibly a simple way of doing that).

And in any case, you can’t get rid of providing that information to people who will possibly use your tools. Personally, if I had to choose, I’ll use the tool that tells me the whole story because I don’t want to discover too late that “… oops, we said we support OpenAPI 3, well, … not totally, we don’t use the security definitions … and we do not support multi-document specifications”.

To be continued

This post is just the first one on that topic, the relationship between specifications and tools. There will be probably more to come as I investigate more on the concepts of implementers’ experiences and specification implementation scorecard/notation/evaluation.