3 dimensions to consider for a successful API-First strategy Series - Part 3

Don't organize APIs against ownership

By Arnaud Lauret, March 30, 2022

It doesn’t matter how APIs are organized, in layers, by business domain or any other dimension if you don’t take care of the most important one. The one dimension that rules them all: ownership. This post is the third and last of the “3 dimensions to consider for a successful API-First strategy” series.

Banner by my partner in crime Mister Lapin.

3 dimensions to consider for a successful API-First strategy Series

When talking about “organizing”, “classifying” or “categorizing” APIs, the private/partner/public classification is the one that comes first very often. But that’s not the only way of labeling APIs and this classification alone is far from sufficient to understand the implications of making APIs a first-class citizen in your organization.

In the past years, when I was advocating APIs to business and IT people in a company engaged in an API-First journey (though it has decades-old legacy systems), I very often described APIs being organized in 3 dimensions in order to help them discover and grasp some important API-first challenges and benefits: API Layers, Business domains (or capabilities), and Ownership.

- 1 - Organizing APIs in System, Business, and Experience Layers

- 2 - Organize APIs around business domains and capabilities, not tools

- 3 - Don't organize APIs against ownership

In this post, we’ll talk about the importance of ownership in the organization of APIs.

Disaster waiting to happen

I did quite a lot of API design reviews. It went pretty well, but some were more chaotic than others. There were different reasons for that, one of them being ownership issues. Every time I encountered such problems, it ended pretty badly.

An API project

The ownership issue example I use the most probably because it made me realize that an API cannot be handled through projects (actually, it was a SOAP Web Service).

The API in question was the one allowing access to contracts, and there was a “read contract” operation (something that would look like GET /contracts/{contractId}). It had been created for Project A by Project Team A (that was disbanded after the project). As Project A only needed a few properties of a contract, like its number and name, Project Team A decided that this operation would only return those data.

Project B came a few weeks after Project A had been released. Project B also needed to read a contract, but they needed the contract’s product category. However, being an essential piece of information, whatever the context, it was not returned. Project B had to modify the operation to add that information but only those one; that way, Project C would have some work, another project cycle would start.

Some may think that’s not a big deal, but each project took a little longer and so cost more money because “read a contract” had to be modified repeatedly. Also, the resulting APIs after a few projects are usually not the best in class.

No business decisions possibles

Another one that I have seen often in the past years is when there are silos that feel like there are 3 meters thick reinforced concrete walls between business and IT.

When I do an API design review, I ask many business/subject matter questions, and I often challenge the needs that led to the API’s creation or modification. Not that I know everything about all subject matters, it’s even the contrary. But I’m must ensure that people in charge have identified the proper needs. And if I can’t understand what the API does and why, how are its future users expecting a “something for dummies” API will? Sometimes these discussions lead the team to actually question the needs. But if the “business” won’t change their mind and consider the team building the API just executors, that only leads to terrible APIs.

No development capacities

Another example that I met only once but marked my mind. I remember a review that went very well. The conversation with the designer was smooth. The first version of the design was not as good as it could have been regarding needs that needed to be represented and guidelines conformity, but everything was easily and quickly fixed. The designer understood all feedback and learned in the making. That was a great review, but problems started after.

Working in Team A, the designer was also supposed to be the API owner. Because of some security and architecture constraints, it had been decided the API would be developed using different technology and infrastructure that team A was used to. The development was delegated to Team B, with which they happen to work with sometimes. Team B frequently built UI on top of the system managed by team A (mainly directly using their database). Also, Team B was supposed to be the first consumer of the API.

What happened? Team B started to build the API precisely like they wanted, absolutely not taking care of the design made by the API owner. They did not care about the API design guidelines and common practices, but worst: usability and reusability were not a concern.

Hopefully, it didn’t last long; the API owner stopped everything and made the necessary to be able to expose the API they wanted to create on their side.

No good APIs can exist without true ownership

So based on my experience, I can say that no good APIs can exist without true ownership. But what does it means?

Defining API ownership

An API must be a product, not a project. It is something that fulfills greater needs than projects ones. It is thought on long-term.

Corollary to the API being a product, an API must belong to a single team. A single team owning the API ensures a long term vision that will fulfill all the needs of all current and future consumers and ensure consistent evolutions

This team can make business decisions. Some business owners/stakeholders must be integrated into the team or they must listen to the team in order to build the best possible product.

And last but not least, this team has full control over API developments. Either because the team has the full capacity to develop them or because it has full control other the hired contractors/third party (who will do exactly what is expected).

The combination of all these elements defines API ownership.

Conway’s Law

Such organization around ownership will irremediably be driven by Conway’s law. An adage that states our systems organizations mirror their own communication structure. It applies at 2 levels: human organization and technology organization.

A company will be divided into various sub-organizations, it affects people and tools.

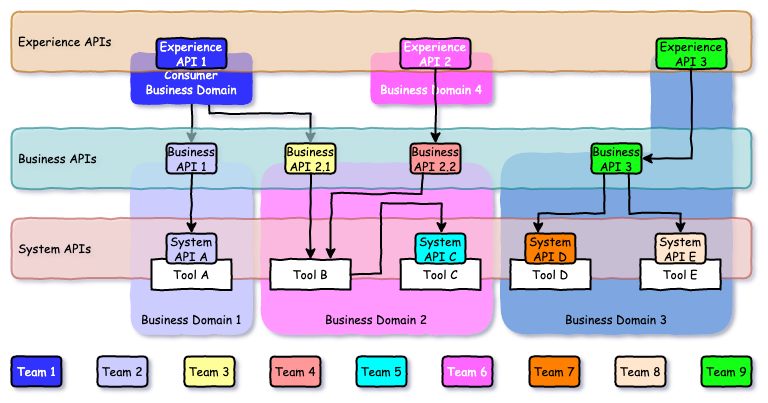

Inside those sub-organizations, in some ideal contexts, a single team may be able to handle a whole business domain (see Business Domain 1 or 4 in the figure), including all of its APIs, even the most hidden one. But that’s not always the case.

If a business domain is too big (see Business Domain 2 in the figure), its APIs will have to be distributed among several teams. But that will require some synchronization between the teams in order to keep a certain level of consistency between the various APIs of the domain, especially the ones that are exposed outside of the domain.

It is not that rare to have various technology used inside a domain (see Business Domain 3). Imagine having a good old commercial off the shelf vendor solution, requiring very specific knowledge), it would be wise to let it be in the hand of experts that will just concentrate on making it run and expose system APIs and have another team dedicated to the creation of business APIs using a more common technology (like NodeJS, .Net or Java for instance).

3 dimensions

That concludes this series describing 3 dimensions of API organization:

- API Layers: 3 different types of APIs with different purposes (system, business experience). Only the business layer is required.

- Business domains and capabilities: Organize around business domains and not tools to create independent and reusable APIs fulfilling business needs without exposing all domain features (and so its complexity). An API is a domain or a sub-domain for dummies.

- Ownership: Each API must have a single owner with full power from decisions to implementation. Take Conway’s law into account when defining the teams managing the APIs.