Hacking an Elgato Key Light Series - Part 1

Hacking and reviewing Elgato Key Light API with Postman

By Arnaud Lauret, February 16, 2022

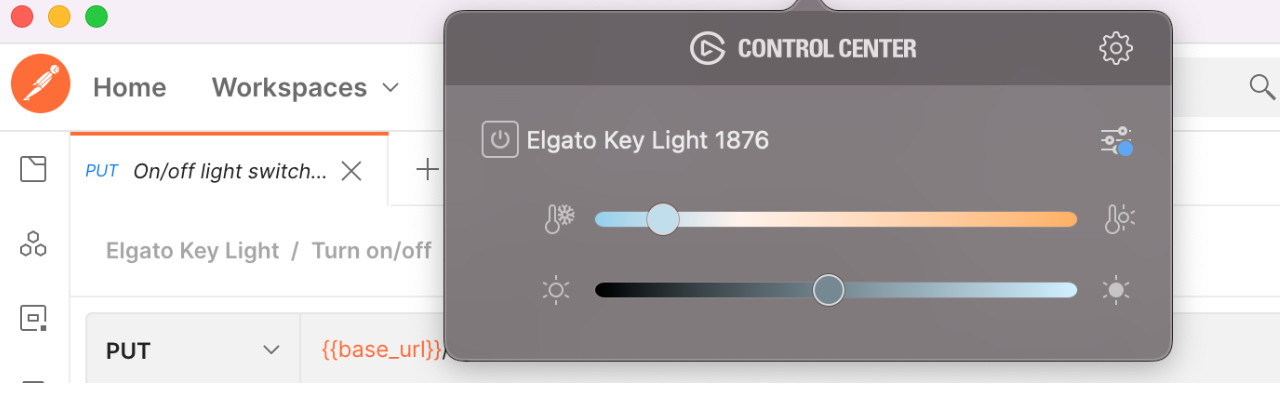

Want to learn how to hack a desktop app calling an API and learn some API design principles? This post is made for you. When I got my Elgato Key Light, my first questions were: “can I control it without using the official control center using an API?” and “is the API easy to understand and use?”. Thanks to Postman’s proxy feature, I was able to easily hack the API. But I was also able to review it in the making, and there’s some interesting API design learnings to share.

Why this post?

I recently joined Postman (the company) and while I have been using Postman (the tool) since its creation, I didn’t much used it the last 4 years as I was spending most of my time doing API design reviews and not much using APIs. I forgot many things, and during that time Postman has evolved a lot! So, I my goal is to (re)learn how to use (and hack) extensively Postman. Instead of keeping all that for myself, I’ll share my learnings in multiple blog posts.

As I just received an Elgato Key Light to enhance the quality on my video calls and video recordings (that’s worth the investment!) and as this device comes with an API, I thought “Hacking my Elgato Key Light” was the perfect topic to start (re)learning how to use Postman. Everything explained here and in future posts should be reusable “as is” with the other variants of Elgato Lights. And if you have other connected devices coming with desktop control application, you should be able to do what I’ll show you with them.

And as always, this post is not only about using a tool, we’ll talk about some API design principles in the making!

Discovering the Key Light API

To control the Elgato Key Light, you can install the Elgato Control Center on you computer (Mac or Windows), there are also iOS and Android apps. In order to hack the Elgato Key Light, I need to discover what requests can be done. To do so, I captured the HTTP traffic going out of the Elgato Control Center desktop application using Postman as a proxy.

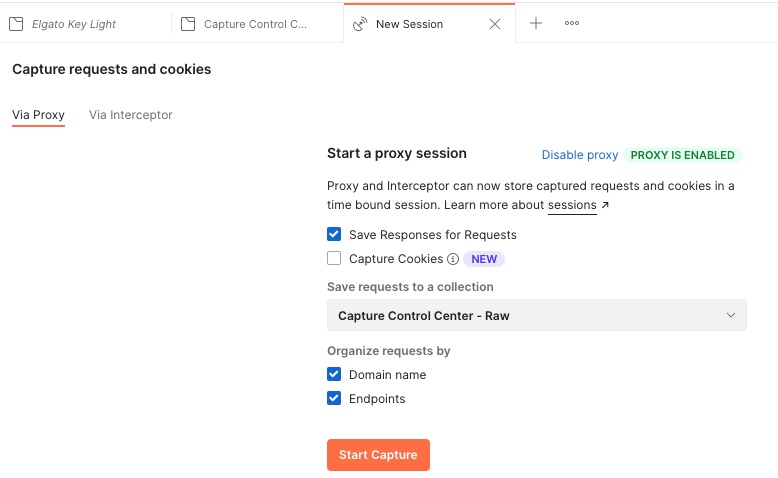

Setting up Postman Proxy

With Postman, you can intercept HTTP traffic in 2 different ways, the Interceptor that runs in Chrome or the Proxy that can be used to capture any HTTP traffic on your machine. We will use the second option.

The whole documentation is available here: Capturing HTTP Request. Here’s a light recap of what I did on my Mac:

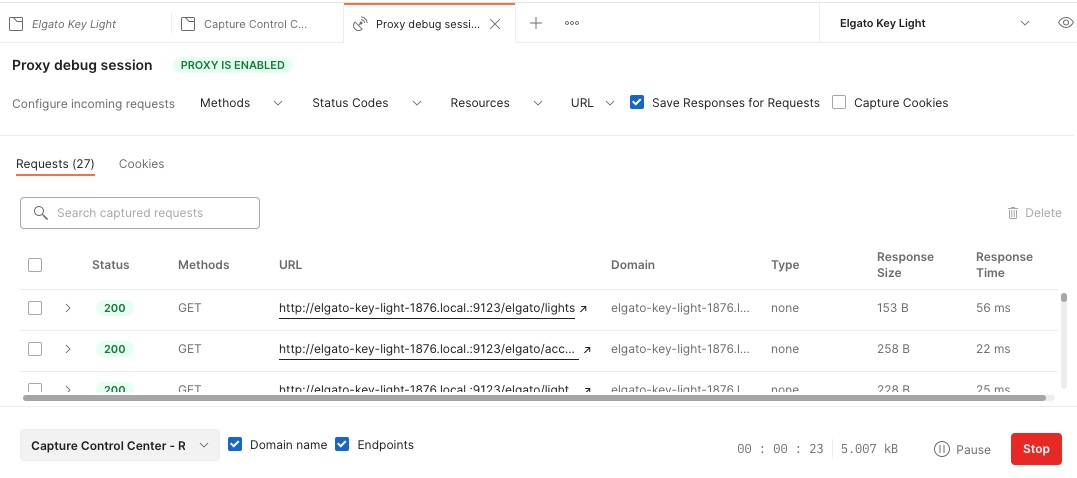

Configuring Postman

- Start Postman

- Create a “Hacking Elgato Key Light” workspace

- Create a new collection “Capture Control Center - Raw”

- Start proxy with “Capture requests and cookies” in status bar (bottom right)

- Use “Via Proxy”

- Check Save Responses for Requests

- Click “Enable Proxy”

- Keep 5555 port

- Click on enable proxy

- Now “Proxy is enabled”

- Save requests to previously created collection and choose “Capture Control Center - Raw”

- Check “Domain name” and “Endpoints” in “Organize requests by”

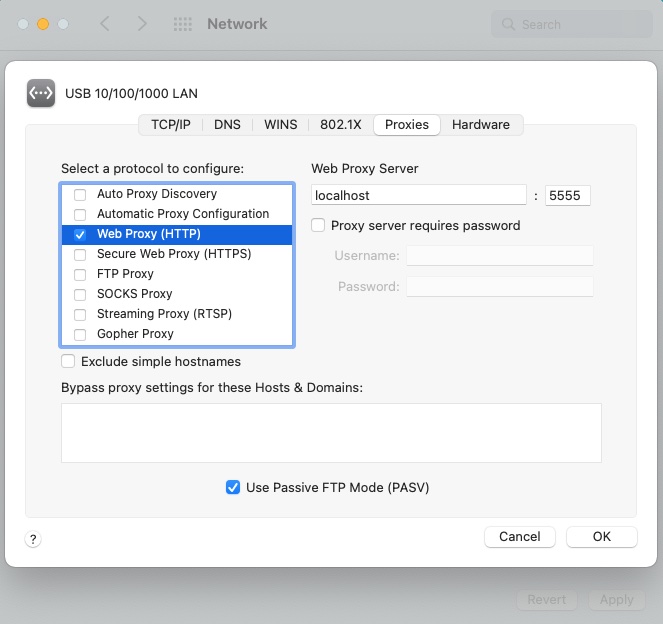

Configuring OS

Note: I’m using a Mac, but it shouldn’t be that different on Windows.

- Open “Network” in System Preferences

- Select your first network interface

- Click on “Advanced…”

- Go to “Proxies” tab

- Check “Web Proxy (HTTP)”

- Set Web Proxy Server host and port to

localhostand5555 - Remove local adresses patterns from “Bypass proxy settings for these Hosts & Domains”

- Click “OK”

- And don’t forget to clik on “Apply”

Now we’re ready to capture HTTP traffic.

Capturing (too much) HTTP traffic

Back in Postman, click on the “Start Capture” button and play with the Elgato Control Center. You can turn on or off the light, change brightness and temperature.

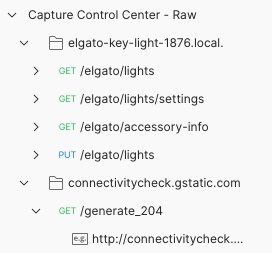

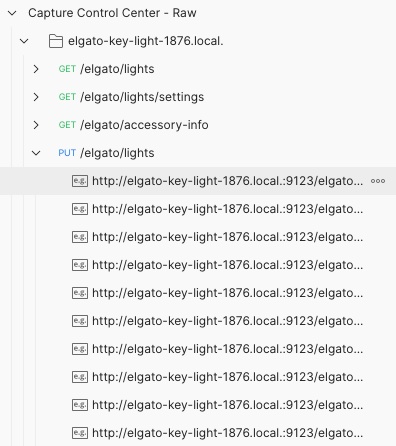

Once done, click on Stop and you’ll find all requests in the “Capture Control Center - Raw”. Requests are organized by domain and endpoint, each request being materialized as an example.

That’s pretty neat, I have a good overview of the requests done during the capture. But I have 2 problems:

- First, there are request coming from another application (Chrome)

- Second, there are many request examples as you can see below

While it’s not really a problem for the GET requests, it’s more annoying to understand what is done with the PUT one.

Capturing (the right) HTTP traffic

In order to avoid being poluted with too much requests, let’s try something more subtil.

First, let’s start a new capture but with some changes in the configuration.

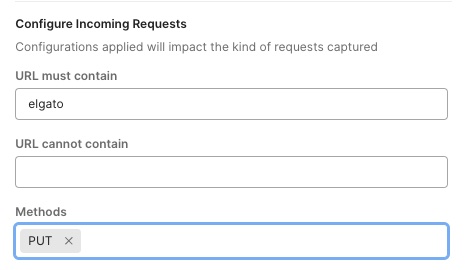

To only get traffic for the Key Light, set “URL must contain” to “elgato”.

And to keep only PUT requests, add PUT to “Methods”.

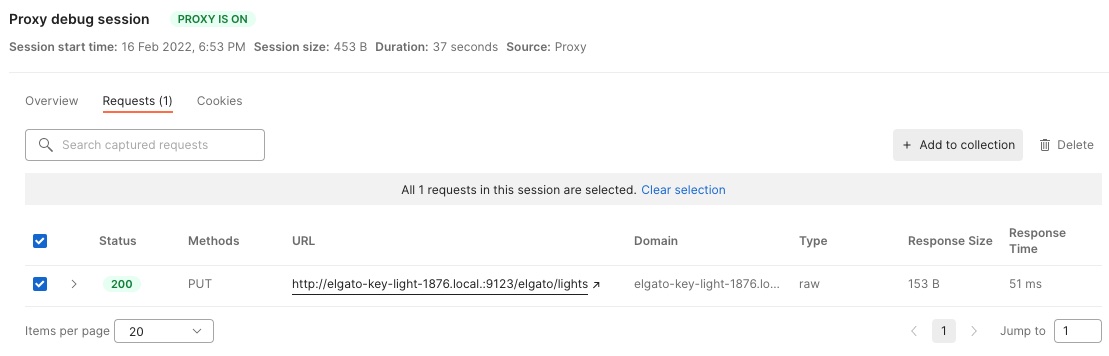

Then, when using the Elgato Control Center, let’s do one thing at a time.

- For instance, turning the light on

- Then go back to Postman, and stop the capture

- Check the request (checkbox before Status)

- And click on “+ Add to collection”

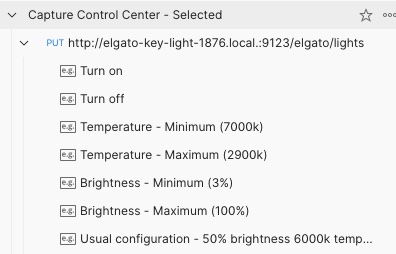

- Create a new “Capture Control Center - Selected” collection

Now go to the newly created collection and rename the cryptic example to “Turn on”. You can do that for “Turn off”, “Set temperature to maximum”, … Everything that comes to your mind. You can also capture multiple request and select a subset to add them to the collection.

Now we have everything to play with the API, we just have to copy/paste/modify the requests.

If you run into strange 400 errors, check if you don’t have a hard coded content-length (yes without caps) in your request headers.

They come from the HTTP traffic capture and are not overrided by Postman (because “you” set them).

Reset OS proxy configuration

Don’t forget to reset your OS proxy configuration once you’ve finished!

Reviewing the Key Light API

Thanks, to the capture HTTP traffic sessions, and taken for granted that the base URL of all requests is http://device-name.local:9123/elgato, we know that the Elgato Key Light API proposes the following operations:

GET /accessory-infoGET /lights/settingsGET /lightsPUT /lights

We’ll focus this review on GET /accessory-info and GET/PUT /ligths.

The neat GET /accessory-info entry point

Looking at this operation’s response (below), we see some basic information like the product name and more technical information like some firmware information.

What caught my eye is the features list, it contains a lights value.

Based on other requests which paths start by /lights, I can guess that if one day I get another Elgato product with an API I can give a try to GET /accessory-info, look at the values in features, which could be “something” and then try a GET /something, PUT /something and possibly GET /something/settings.

It’s not an hypermedia API, but at least it provides some hints that help you to use other Elgato APIs.

{

"productName": "Elgato Key Light",

"hardwareBoardType": 53,

"firmwareBuildNumber": 200,

"firmwareVersion": "1.0.3",

"serialNumber": "BW21K1A01548",

"displayName": "",

"features": [

"lights"

]

}The not so neat GET and PUT /lights

The following body is used by the Elgato Control Center when modifying the light status.

{

"numberOfLights": 1,

"lights": [

{

"on": 1,

"brightness": 50,

"temperature": 143

}

]

}It is composed of 3 pieces of information:

on: Indicates if the light is on (1) or off (0)brightness: The brightness level in % from 0 to 100temperature: A quite cryptic integer representing the light temperature which goes from 2900K (344) to 7000K (143)

When non human readable status is not a problem

While I usually prefer human readable strings for such status (like “on” and “off”), that’s still easy to understand. Especially in that case where there are only 2 values. Also, it’s fairly common to have on and off represented by 0 and 1, so Elgato follows a common practice, that’s good. And actually, when you have to use those values in code to turn the light on and off, that’s actually pretty convenient. So when designing API, think about understandability by humans, but also usability in code.

Simple consumer side business rule

Strangely (or not), the application limits the bounds of brightness to [3,100].

But I was able to set brightness to 0 with Postman, it actually turns the light off (without changing the on value).

Maybe the API should handle that and manages those boundaries if that’s important.

Never let consumer deals with provider’s business logic, even the simplest one, it will be really hard to modify it in ALL consumers and may lead to problems (hopefully I didn’t ruin my Key Light).

Silent error

By the way I also tested to set brightness to 110%.

I didn’t got a 400 Bad Request as I expected but a 200 OK!

The Key Light didn’t exploded hopefully.

Actually, the brightness was not modified, it kept its previous value.

That’s a bad design, as a consumer/user, the API didn’t warned me that I sent a value that will never ever be accepted.

So better return an explicit error.

Terribly complex consumer side business rule

That’s the worst part of the API, at least until I get more information about light temperature. To control the temperature, the Elgato Control Center App proposes a slide which goes from 7000K to 2900K (K is for Kelvin). But when it calls the API to change the temperature, it’s not 2900, 6000 or 7000 that is sent but 344, 167 or 143. I check a few values to understand what was the correspondance and realized there was some voodoo-non-linear-maths-physics magic involved. That means consumers have to know some internal business logic that MUST be provider’s business only. That’s a terrible idea, it makes the API really hard to use (and again: what will happen if the business rule has to evolve?). Hopefully, I’m sure I’ll find a way to make that more simple with some Postman magic.

Convenient partial modification

Last but not least, you’re under no obligation to send everything in the PUT body.

That may raise some HTTP-extremists’ eyebrows, but I find this really convenient.

That way, I can just turn light on without having to know current temperature and brightness with the following body that got rid of numberOfLights, brightness and temperature.

Maybe providing a PATCH would make this request more HTTP-compliant.

Your private API is not so private

By the way, what I’ve done here is a good reminder about “your private API is not so private”. So be careful about how you design it in order to, at least, block consumers doing things that could harm your providing system and, at best, to provide a simple to understand and simple to use API, even for those who are not supposed to use it.

To be continued

As you can see “hacking” a desktop application that sends (unsecure and local) HTTP request is quite simple with a proxy (there are other tools than Postman to do so, for instance I remember using Burp Suite a long time ago). With what we’ve done we can easily create requests that will do what we want by just copy/pasting/modifying the examples resulting from the HTTP traffic capture. I’m working on a complete collection allowing to control the Elgato Key Light and doing so I used a few tricks that I’ll show in future post(s). In the meanwhile, you can already see what I’ve done by clicking on the button below.