Handle API gateway and backend differences in API documentation with OpenAPI Specification

By Arnaud Lauret, December 15, 2021

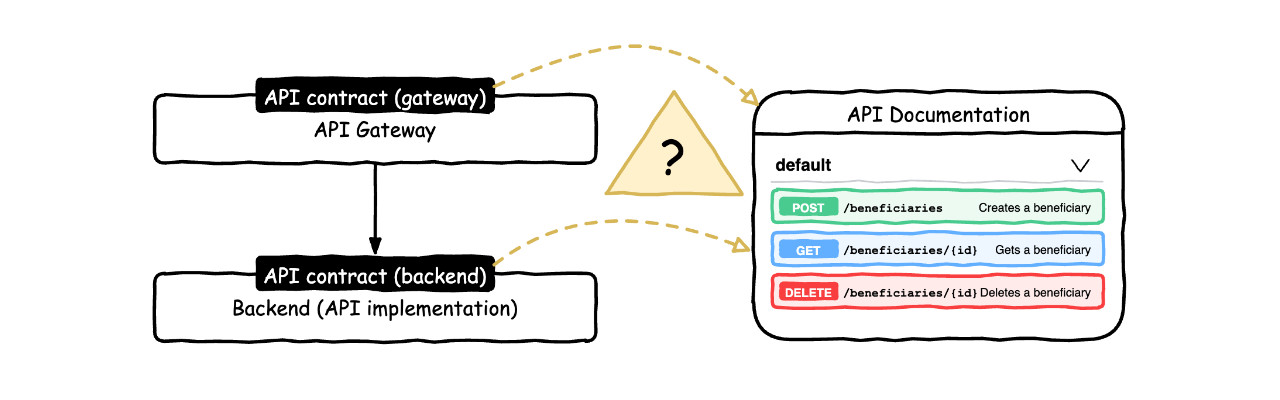

I got yet another interesting question from my social networks: how to deal with the fact that an API contract can be different at gateway and implementation levels, and more precisely how to manage that when describing that contract with an OpenAPI file used as specification targeting API’s implementation’s developer and documentation targeting API’s consumers?

The question

The original question was this one: “I’m trying to work out how to use OpenAPI both as a service spec (with code generation) but also as documentation when the service will be deployed behind a gateway that will return some HTTP responses (401/403). Do I write in the OpenAPI spec what the end user sees (that an endpoint might return 401 say) even though the underlying service isn’t implementing that call? It makes the code generation ‘wrong’ but equally the developers need to know that the gateway configuration should protect it. Or do I make the OpenAPI reflect the service, in which case how do I tell the end users that they may see additional errors?”

So the question is how to deal with the fact that an API contract can be different at gateway and implementation levels, and more precisely how to manage that when describing that contract with an OpenAPI file used as specification targeting API’s implementation’s developer and documentation targeting API’s consumers

To answer that question, we need to talk about API gateways and how they can expose an API contract that is slightly different from the implementation’s one.

How contract can differ between gateway and implementation

Note that for this post we’ll consider the gateway as as “smart-dump pipe”, and so set aside the “heavy transformation” use cases that are not relevant here.

An API gateway is a proxy that sits between backends providing APIs and their consumers. Such proxy is useful to avoid reinventing the security wheel. With an API gateway, dealing with the Oauth dance and ensuring that only registered consumers can use some API is just a piece of cake (though that does not mean it does ALL security job as shown in my previous “An API Gateway alone will not secure your API” post). Other less known feature, gateways also provide throttling to ensure that a given consumer doesn’t do more than X call per second on a API or to ensure that a backend does not take more than Y call per second to protect non scalable infrastructure.

Errors and more

Doing such stuff independently from the API implementation, an API gateway actually modifies exposed API contract.

Indeed, if a consumer makes an API call without an access token, they will get a 401 Unauthorized response coming from the gateway, their API call having not reach the backend.

Same goes if a consumer goes beyond the X call per second, they may get a 429 Too Many Requests coming from the gateway.

Those errors are not part of the original contract exposed by the backend.

Important notice regarding errors: ensure that errors returned by your API gateway actually follow your API design guidelines.

But the API gateway may modify the contract beyond adding some errors.

As the gateway is a proxy, the server host is not the same at the gateway level (https://cool-domain.com) and the backend level (https://obscure-server-name).

It may change the base path, the backend exposing its API on /api and the gateway exposing on /meaningful-name.

A gateway may also add some HTTP headers in responses.

More tricky, the gateway may change security settings. It’s fairly common to have various security modes available at the gateway level (Oauth, OpenID connect) but between the gateway and the backend a more generic, often JWT based security mode is used.

And even more tricky, you may have some endpoints at backend level that are only used internally and must not be exposed at gateway level.

Impacts on OpenAPI file

All that means the modifications can take place in the following places in an OpenAPI file:

openapi: 3.0

servers:

- url: # Gateway and backend won't have

# same URLs (scheme, host, base path)

components:

securityDefinitions:

# Definitions of gateway specific security

# modes different from backend

paths:

/any-path: # Some paths may not be exposed on the gateway

any-operation: # Some operations may not be exposed on the gateway

security:

# Usage of gateway specific security

# modes different from backend

responses:

429: # Gateway will add or override HTTP

# status codes for all operations

headers:

# Gateway may add specific headersThe answer

So how to deal with that regarding an OpenAPI file used as specification and documentation?

Consumer’s perspective first

First, what is 100% sure is that the consumers (well, their developers) must get access to a documentation describing the API from their perspective, that is the API gateway version.

If the difference between backend and gateway contract is only about getting a few errors like 401 or 429, you could possibly provide the backend reference documentation and have a dedicated pages to explain how some specific errors are handled. But that means when consumers read the API reference documentation, these errors are not explicitly described. And that is a problem in my humble opinion: as a developer using an API, I want to know exactly what happens reading the documentation of an operation.

That means, the reference documentation and hence the underlying OpenAPI file, must include those information. So how to achieve that?

In case of backend specific operations

If your backend exposes specific operations that must not be exposed at gateway level, I would suggest to put them in a separate API. Yes, a single backend can expose 2 different APIs on two different root path. That will avoid the risk of unintentionally expose purely internal admin operations to the outside world.

From gateway to implementation

First option, create an OpenAPI file describing the API at the gateway level and tweak it, if needed, to use it at backend level:

- Replace gateway

serversby backend one(s) - Replace gateway

securityDefinitionsby backend one - Replace gateway operation

securityby backend one - Remove or replace gateway specific

responses - Remove gateway

specificheaders inresponses - Add backend specific operations if you don’t want to separate them (see In case of backend specific operations)

Don’t do that manually, do it programmatically to ensure exhaustivity and consistentcy. You can use JQ or an OpenAPI parser.

From implementation to gateway

The second way of dealing with that problem would be to transform the OpenAPI file describing the implementation’s contract into the gateway one.

In a code first approach, you could use the implementation’s documentation (OpenAPI) generator to do the transformation. If you’re coding in Java, it’s dead simple to do all the modifications programmatically with SpringFox.

In both code first and spec first approaches, you can also do the transformations on an implementation version spec before or during deployment. If you’re very lucky, your API gateway manages that transformation magically (but I doubt that actually exists). If not, proceed like in “gateway to implementation” scenario using JQ or an OpenAPI parser to modify the file.

Whatever the way of doing the modifications, they would be:

- Replace backend

serversby gateway one - Replace backend

securityDefinitionsby gateway one - Replace backend operation

securityby gateway one - Add gateway specific

responses - Add gateway

specificheaders inresponses - Remove backend specific operations if needed (see In case of backend specific operations)

Gateway and implementation

And last but not least: doing both. You can create an OpenAPI file describing the two versions and then strip it of unwanted elements before using it as gateway or backend level. In my humble opinion that seems to be the best solution. Indeed, you actually define explicitly what happens at both level and especially at gateway level (it’s up to provider to decide how to use scope for instance). And when it comes to modify the OpenAPI file, it’s quite simple to remove elements. A middle-ground even better option could be to use templates or script to handle the addition of gateway errors or headers (which are always the same).

Note that using a linter such as Spectral can ensure that your OpenAPI file(s) are actually valid ones (defining all errors for instance).

Consumer first and machine readability

Two important things to remember after reading this post:

- The consumers MUST get a documentation, hence an OpenAPI file, that matches the API they see without bothering them with internal concerns (for instance that “the” API is actually build upon 2 components).

- And whenever you need to tweak the documentation/description of an API, better take advantage of a machine readable format such as the OpenAPI and do the modifications programmatically not manually