How to choose ids and codes to build user-friendly and interoperable APIs

By Arnaud Lauret, December 29, 2021

As an API designer, why should you care about the value of a productId, a countryCode, or an error code?

Because wisely choosing the value of such (in a broad sense) “identifiers” greatly participates in the making of a user friendly API; but most importantly an interoperable one.

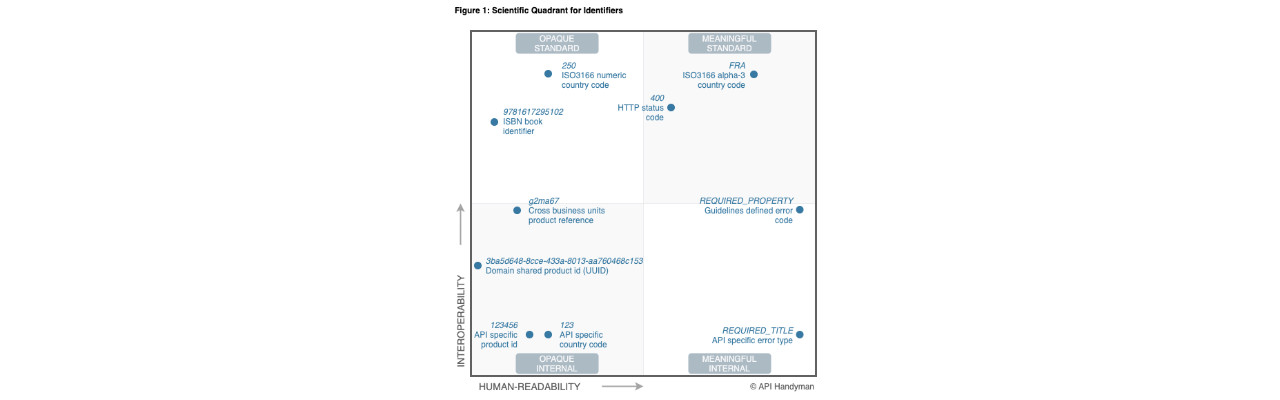

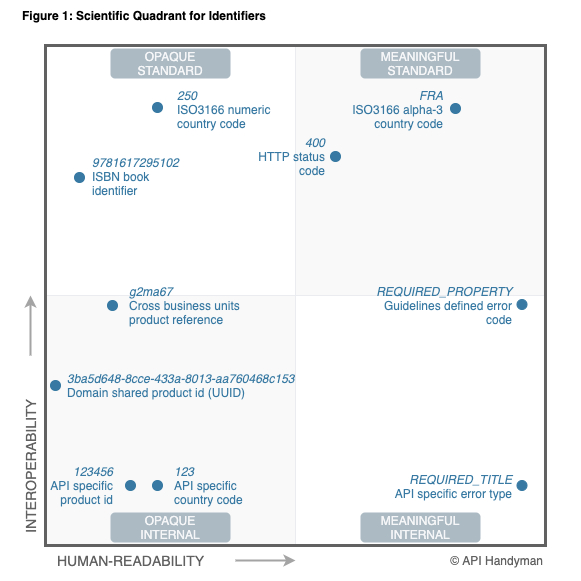

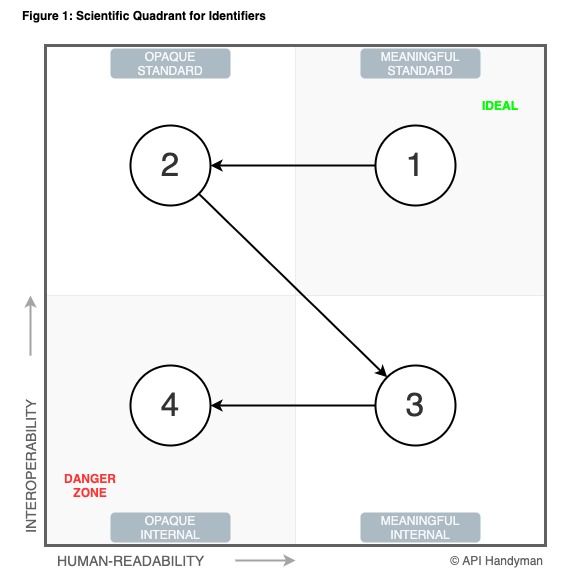

The following “Scientific quadrant” (inspired by Gartner’s Magic Quadrant), shows a few examples of those identifiers sorted along 2 axes, interoperability and human-readability. Let’s analyse those 2 dimensions and those examples more closely to see how to choose “identifiers”.

Interoperability

Interoperability is the ability of software to exchange and make use of information. For instance, switching from file exchange to exposing web APIs is a first (great) step in improving the interoperability of a system. That actually improves how other systems can exchange information with yours.

But does exposing APIs magically makes using information easier for consumers? It highly depends on the actual data exposed (output) or expected (input) through it, and especially its ids and codes.

Internal vs standard

For instance, using a 123 purely internal code to represent a country such as “France” is far less interoperable than using FRA, the widely adopted ISO3166 country alpha-3 code standard.

If GET /authors returns a list of authors with their name and country for instance, it will be fairly easy for any system to interpret a standard FRA country code than an obscure 123.

Indeed, enabling the interpretation by consumers of such a purely internal identifier may require:

- Providing extra documentation, like a (terrible) table of custom country codes and names (seriously don’t do that)

- Or adding an extra operation to the API, like a

GET /countriesreturning all country codes and names or a more specificGET /countries/{countryId}(that’s less terrible) - Or adding extra data, like returning author’s country name along with the code (that make the author’s data self sufficient but less usable for other purpose than just showing them to end users)

But even using one of those “solutions”, if no actual ISO3166 code is ever used, consumer programs will have hard time to actually interpret such specific way of representing countries. Maybe they’ll have to work on country names to match what they know of country on their side (probably ISO3166 based)… hoping country names are actually returned in english and without typos. It can be more a guess than an actual matching. Maybe consumers developers will painfully build a mapping table based on the data they get… But it will need to be updated if new countries are added. I don’t mean actual new countries, that’s a possibility but that don’t happen much, but new authors from countries that were not already represented in the authors list.

On the other hand, using a standard ISO3166 code will makes both consumer and provider jobs easier because they naturally share common identifiers.

Ideally, when I see a GET /authors and as I know authors countries are returned, I can guess that GET /authors?country=FRA will return french authors.

It’s a no brainer, impossible to achieve with a custom country code.

If I use ISO3166 codes on my side, matching my data with the one coming from GET /authors based on countries is dead simple.

And I don’t care if new countries appear in authors data as I rely on the same ISO3166 referential: my consumer is always be up to date.

Well known identifiers

But sometimes it’s not possible to use a “standard” identifier known by everyone in the outside world.

It’s actually fairly common to use custom identifiers, but if that’s the case always favor the “well known” ones.

For instance, if you need a product identifier (for GET /products/{productId}), better use an id shared by a few APIs across a domain or an id shared across the whole organization than using an API specific product id.

A well known product id could be used across various APIs such as “product catalog”, “order”, “shipping”, “supplier”, “storage”, …

The more systems will share the same ids, the better.

It’s basically about using or defining local standards.

Doing so, any system knowing such well known ids can use them with any API inside a domain or the organization.

And note that it’s always good to double check if by chance there’s a standard identifier that you can use.

If the “product” we were talking about reveals to be a “book”, prefer the use of an ISBN standard book identifier than your custom one, even if it is known across your organization (and change your resource name, GET /books/{isbn}).

Indeed, your well known ids are still custom ones and so unknown by the outside world.

Choosing interoperable data that other systems will interpret easily, data that is known by as much systems as possible, is a must do to create successful APIs. But when creating APIs, you do not only deal with programs. There are humans in the loop: the developers who write the programs using those APIs.

Human-readability

Though choosing interoperable data actually makes API more human-friendly, because “common language” and “shared identifiers”, only focusing on machine to machine interoperability without taking care of human-readability could cripple your APIs success.

Obvious

The more obvious values are the better.

A REQUIRED_TITLE error code returned with a 400 BAD REQUEST on a POST /books to add a book is easily understandable.

It’s understandable but quite specific; probably defined at a single API level.

Maybe using a more generic code defined for the whole organization in your guidelines, reusable in many contexts, could be better.

A generic REQUIRED_PROPERTY error code returned with a "property": "title" is more interoperable.

Guessable

A FRA alpha-3 ISO3166 code is better than it’s numeric counter part 250, a human being can guess what it means.

It’s also quite simple to guess other alpha-3 ISO3166 code, for instance, what is the one for Italy?

But that does not mean numeric values are always evil.

Take HTTP status codes, such as 400 or 418 for instance.

They require some basic HTTP knowledge to understand what they mean; any 4XX is an error caused by consumer.

But once you have that knowledge you can guess what means any HTTP status code.

Never heard about 418, no problem, you can guess that’s consumer fault.

By the way, being guessable, or interpretable should I say, like this is also interesting for the consumer program, it actually makes data more interoperable.

Human friendly

Note that creating obvious or guessable values is not always possible, especially when there are countless of them.

Many times, you’ll have to rely on opaque ids, but that does not mean they should be hard to remember or type for us, poor human beings.

An ISBN book identifier such as 9781617295102 is far more human friendly than a UUID 3ba5d648-8cce-433a-8013-aa760468c153 but less than a short id like g2ma67.

And I think that 123456 is more human friendly than all the others.

But don’t forget that interoperability always prevail over human-readability.

In that case, even though 123456 is more human-friendly, it’s still an internal id known only by the system which has created it, while 9781617295102 is a standard ISBN known widely outside of the organization.

How to choose identifiers

So how to choose identifiers, ids and codes? First, try to find the most interoperable ones, and second, try to keep them as much human readable as possible.

The level of interoperability of an API depends on the level of “standardization” of its data. A standard identifier will be easily understood by many systems while an internal one will be understood only by the system creating it. But “standardization” does not always mean “standard” (like ISO country codes), sometimes using well known shared identifier inside an organization or a domain will be sufficient.

The developer experience will also be enhanced when using human readable identifiers; easy to understand, easy to type, easy to remember, easy to guess.