API Days Interface 2020 Series - Part 2

Doing APIs right and doing right APIs

By Arnaud Lauret, July 26, 2020

API Days Interface being online made the experience a bit different but after 3 days, I felt almost as usual; exhausted and my brain boiling. In previous post, I shared my feelings about my first online conference. Now let’s talk about the content; Sam Newman doing a facepalm, API design, architecture, governance and my new favorite quote “Doing APIs right, doing right APIs”.

API Days Interface 2020 Series

INTERFACE, by API Days gathered best past 7 years speakers, entire global community, and the API landscape leaders around our most popular topics. In this 2 part series, I share my feeling attending an online conference and what I learned.

- 1 - Speaking into the void

- 2 - Doing APIs right and doing right APIs

Design

As usual, API design is a center piece of any API conference. Again we had brilliant demonstration of why the API design first approach prevail and I was pleased to see some long awaited features added to the OpenAPI Specification.

| Speaker | Session |

|---|---|

| Mike Amundsen, Author of “Designing and Building Web APIs” and “Restful API Design” | Building great web APIs |

| Alianna Inzana, Senior Director, Product Management @SmartBear | /Contract/{Collaboration}/DrivenDevelopment |

| Darrell Miller, Board Member of Open API Initiative | The State of Open API Specification |

Design first

Both Alianna Inzana and Mike Amundsen did a wonderful job describing the API design and build lifecycle and both especially said that design forst approach is key.

An API must be created to solve business problems for people. In order to be sure that you build the right API and so identified the real needs, you must use a design first approach and request feedback early. Using a standardized API description like the OpenAPI specification and creating mocks will make it easier to check if you’re doing the right API. By working on a design and not an implementation, you can do modification easily and quickly.

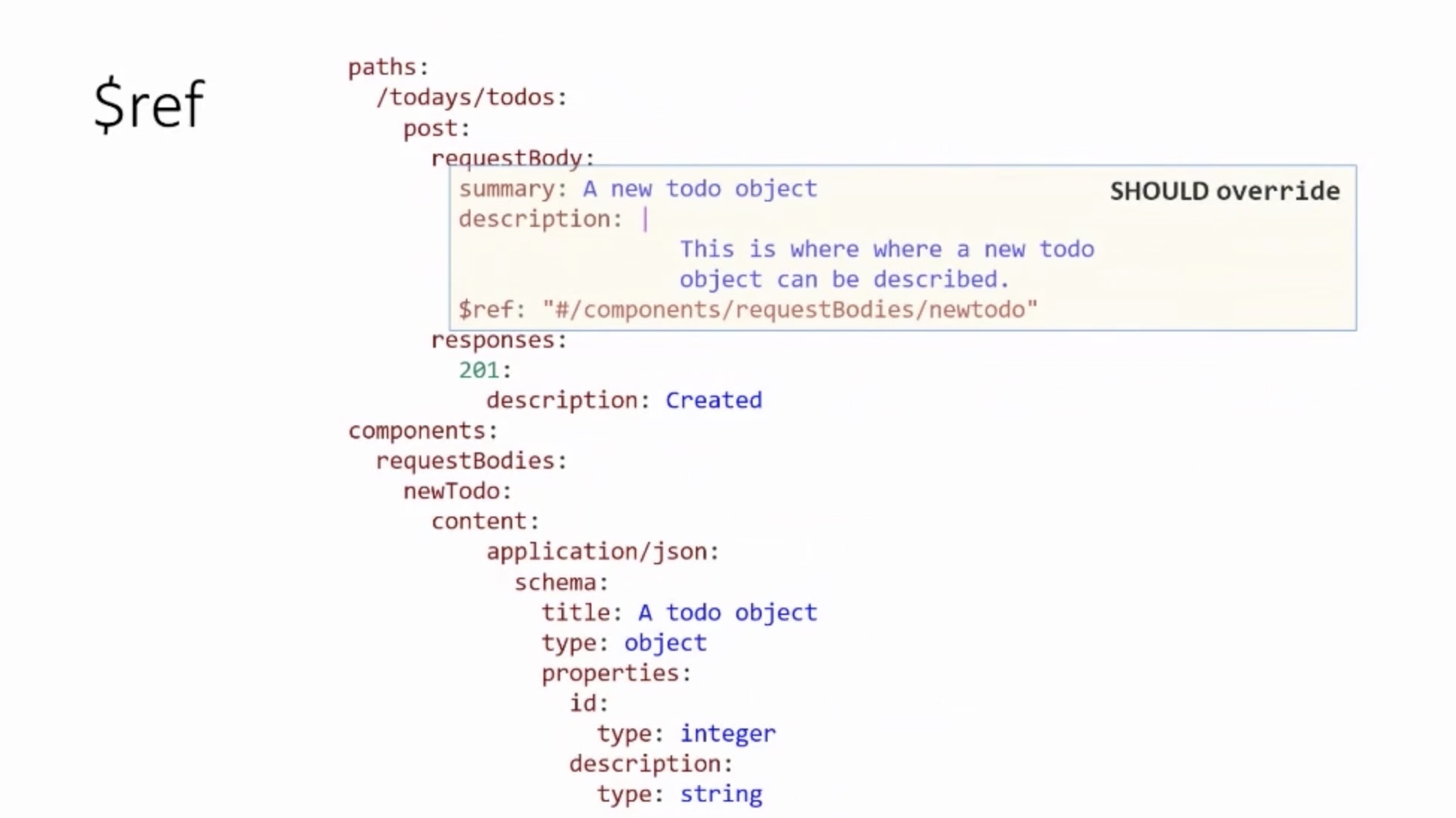

OpenAPI Specification improvements

At a more ground level regarding API design, Darrell Miller made my day by announcing two major improvements coming with version 3.1 of the Open Specification (among other modifications):

OpenAPI 3.1 supports original and standard JSON Schema in its latest version, no more fancy OpenAPI/Swagger variation

And at last we’ll be able to have a description (and all other possible properties) along with a $ref. Any property set beside the $ref will override what comes from the $ref.

Architecture

APIs and their implementation are nothing without good architecture reliying on clearly identified and understood principles. And they are nothing without organization around them. This conference proposed some sessions that were really good at talking about this.

| Speaker | Session |

|---|---|

| Mary Poppendieck, Author of “Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit | Where do great architecture come from |

| Sam Newman, Author of “Building Microservices and Monolith to Microservices” | Microservices, APIs, and the Cost Of Change |

| Mark Cheshire, Director Product Management for API Management @Red Hat | When to manage Microservices as a Mesh or as APIs? |

| Ronnie Mitra, Author of “Microservice Architecture” | The Next API Strategy: Going Borderless |

| Matthew Reinbold, Director, Platform Services Center of Excellence @Capital One | APIs are Arrangements of Power. Now what? |

Principles and responsability

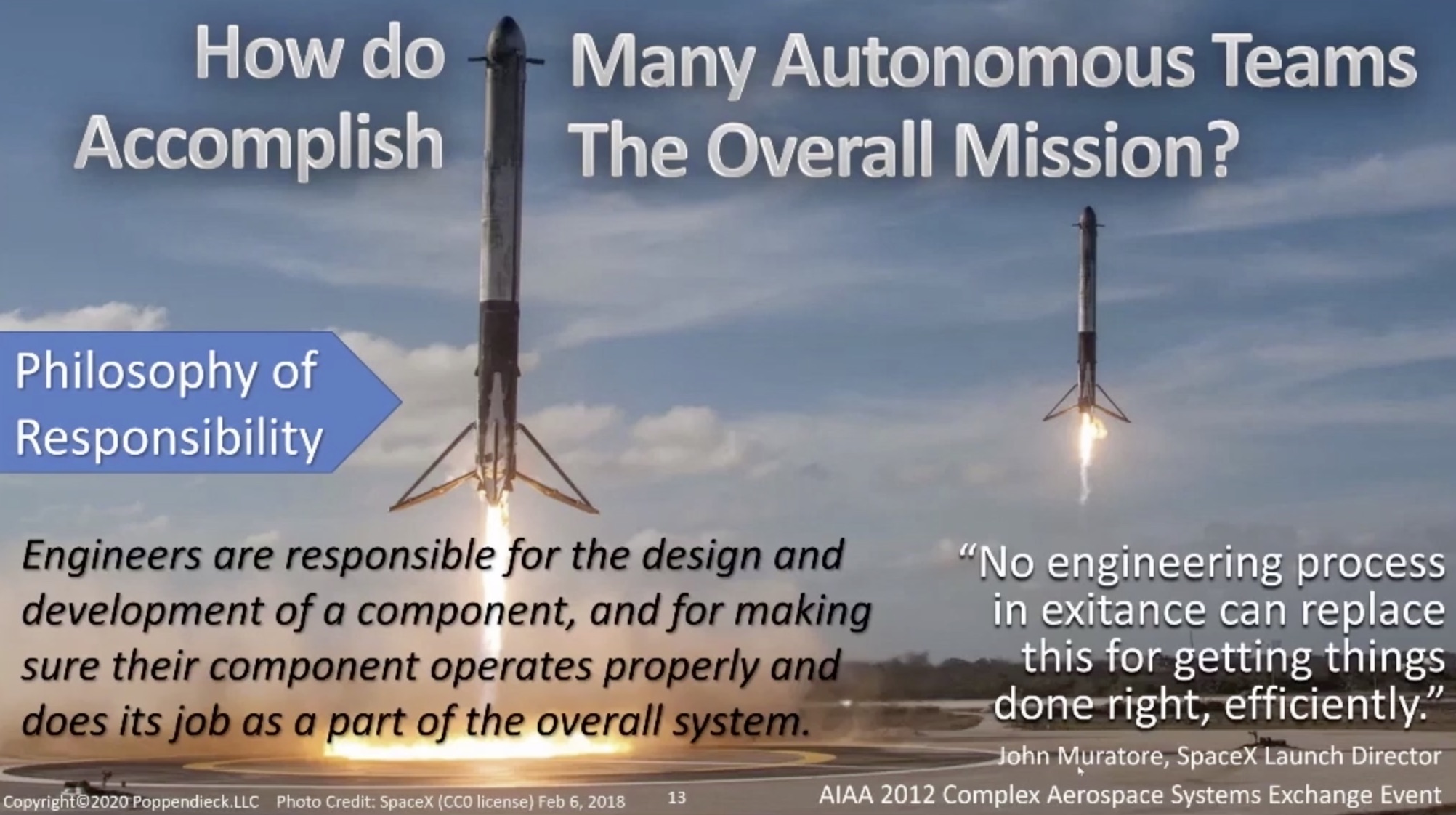

Mary Poppendieck gave an amazing talk about evolution of architectures from the 60s to our time with her Where do great architecture come from session. It’s a pity she didn’t have more time, hopefully she may come back at another API Days with a longer slot. I will not retrace here in details all what she said (if you watch only one video of this conference, this is the one).

In order to build better systems we can rely on principles discovered throughout the years thanks to past failures:

- Redundancy: instead or running one instance, run many

- Fault isolation: when a component fails, others can still run

- Local contral: gives each component the capability of running on its own even when it relies on others (caching results for example)

And we are still discovering new principles even when relying on old ones. For example in 2000, Google solved a major crisis (indexing software stopped working due to faulty hardware). By combining redundancy and fault isolation principles, they build an architecture composed of cheap machines that tolerates such failure. In 2010 Amazon make a ground breaking evolution by getting rid of the sacrosanct central database and building a distributing database.

Another interesting aspects is that some architecture principles are not only related to software or hardware. They can be related to organization and people too. And actually, with systems being more and more complex, archicture decisions are mostly people related.

In 2000, Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s CEO, believed that his company (and the underlying system) couldn’t become huge without encouraing team autonomy, hence the famous memo.

Teams must be autonomous but do be efficient they need to understand that they are part of a bigger system. Their mission is part of an overall mission.

Microservice vs API

Sam Newman gave a definition of a microservice and how it relates to API; this is important to remind because the “microservice” name tend to be used for things that are actually not “microservices” and also because APIs and microservices are too often confused:

- A microservice is independently deployable

- A microservice runs as a separate process

- A microservice’s data are hidden inside its boudaries

- A microservice can be called via some form of network call: for example via an API which becomes a mean to hide internal implementation.

So the microservice is not an API and reverse. The API is only an interface to a microservice. Also, if your “microservices” share a database with others or are wars or ears running inside a Jboss server for example, those are not microservices.

Versioning Handling changes

Sam Newman gave a deep dive into versioning during his session. He especially explained that versioning is not the real problem. It’s not about version 1 and version 2. The real problem is how to handle change, how to handle backward compatibility and incompatibility. And this is even more true when doing microservices which are supposed to be independently deployable: maintaining backward compabitibility is key.

He gave 4 concrete tips to do so.

I have to admit that I was quite proud of myself because I realized that I always say what he told us during my API Design reviews!

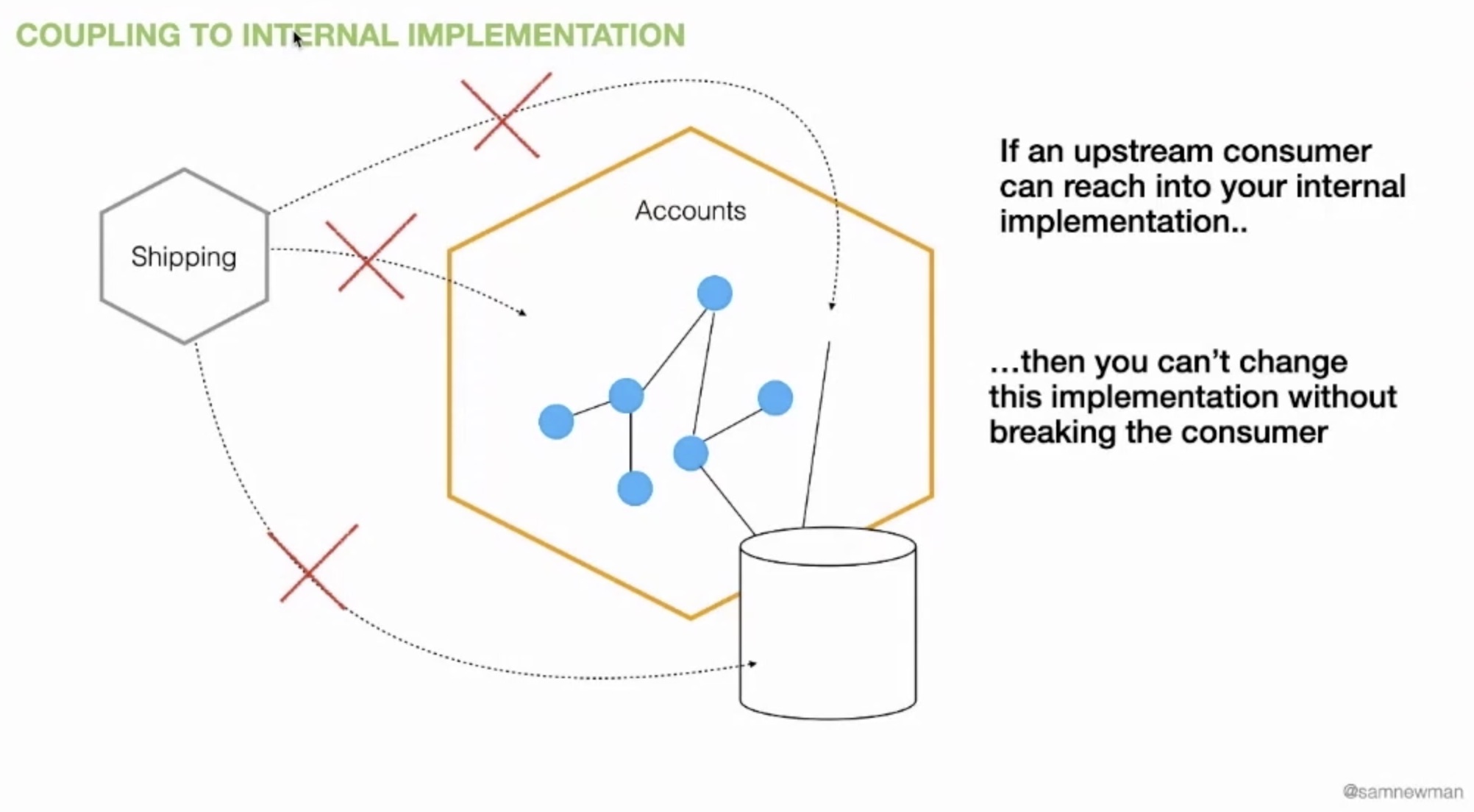

Tip #1: Hiding information is key.

If an upstream consumer can reach into your internal implementation then you can’t change the implementation without breaking the consumer. Consumer and provided are tightly coupled, making any change risky and even impossible.

Modularization is not a new concept that appeared with APIs and microservices. In 1971, D.L. Parnas published On the criteria to be used tin decomposing systems into modules. He looked at how best to define module boundaries and found that “information hiding” worked best.

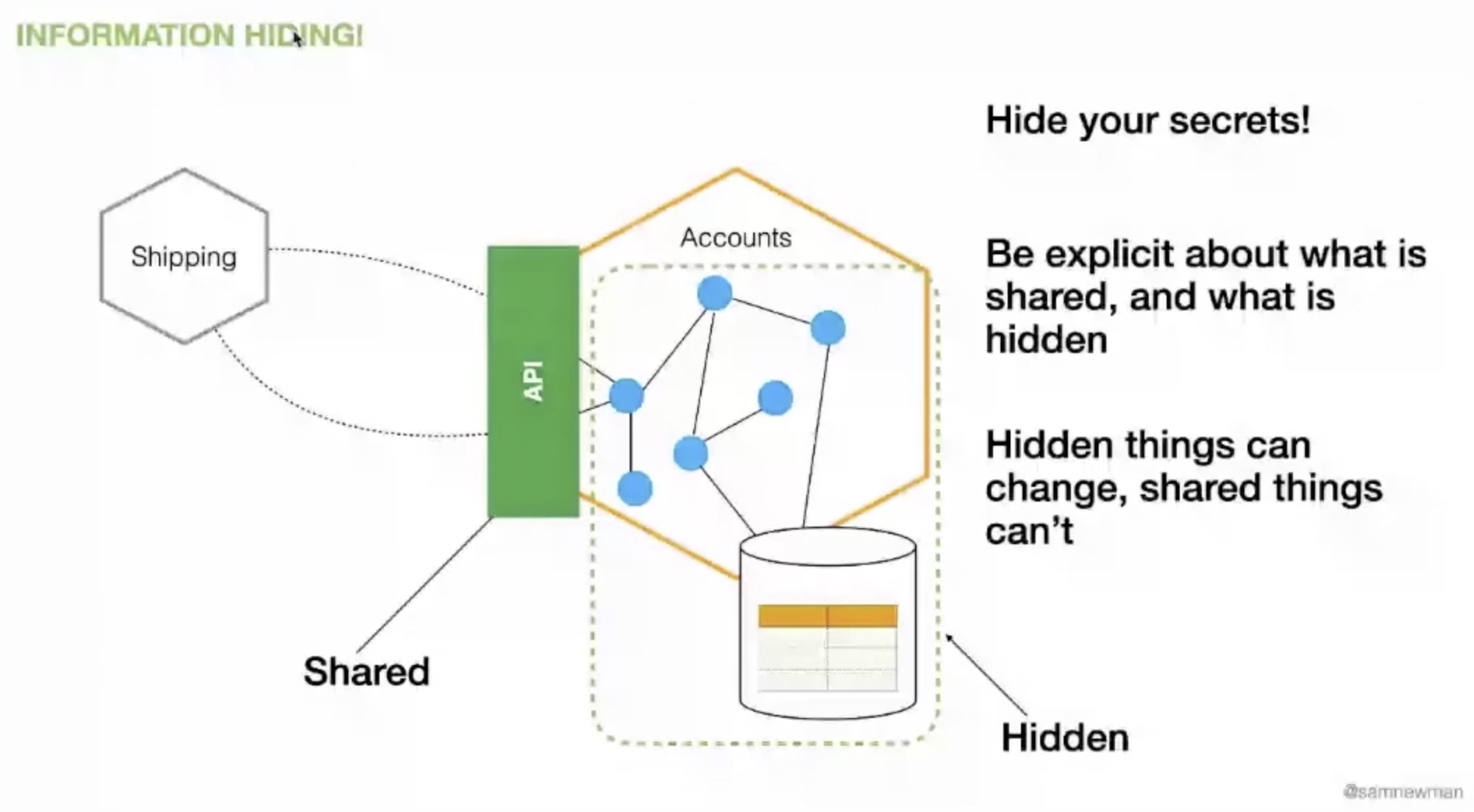

Your interface (API) shows what is shared, the rest data and implementation details is your own business. That’s why it is really important do have separate models for data, objects and exposed interfaces (as also always say Mike Admundsen).

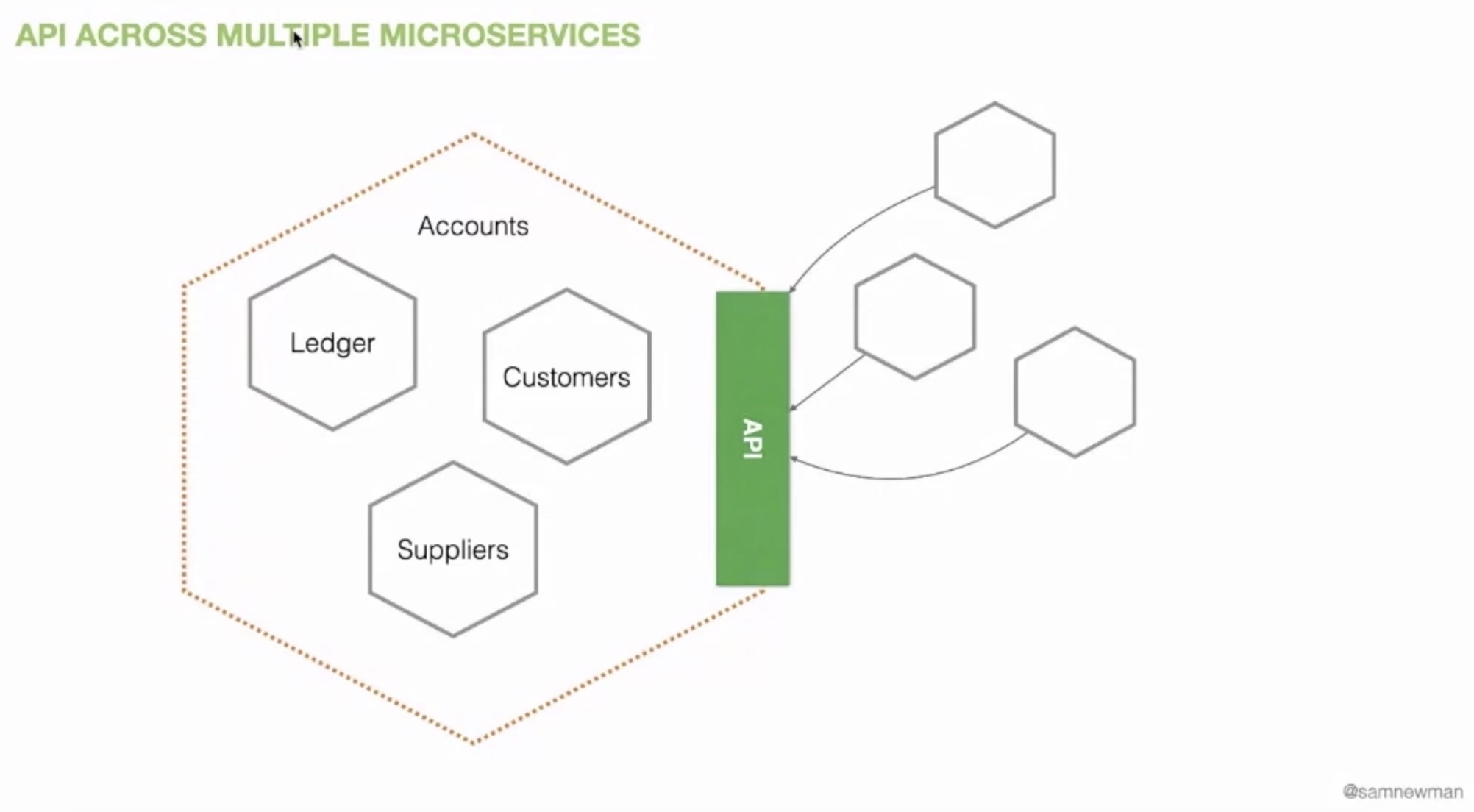

If the whole becomes to big, you can split your internal implementation in various sub modules, while keeping the shared interface unique and unmodified. But be warned that only works if the whole set of microservices/modules is handled by the same team.

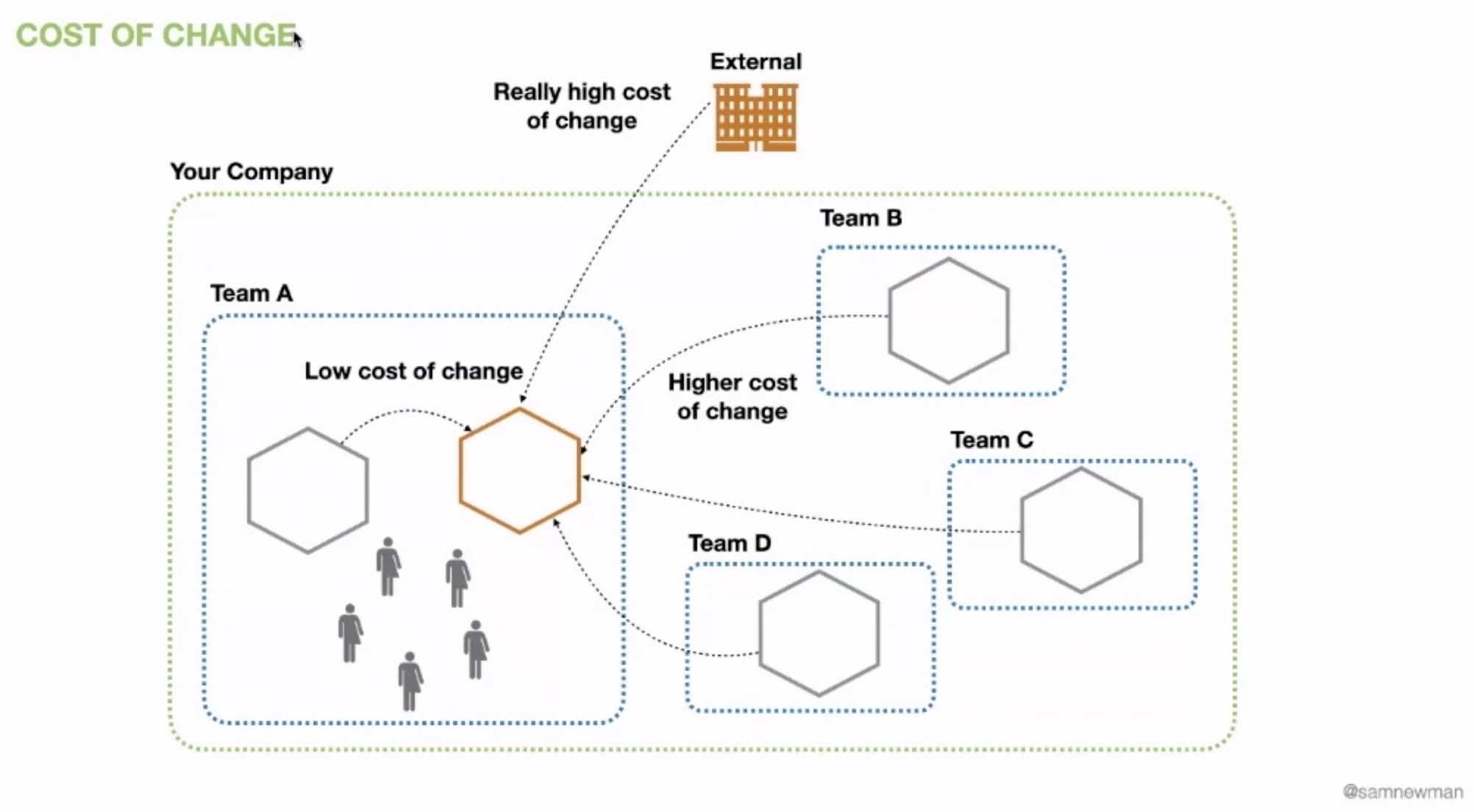

Tip #2: Cost of change varies

Not all changes have the same cost. Some changes have critical consequences and some others have very limited impacts.

A modification inside a team, on the set of microservices of the Accounts domain above for example has a very low cost because it only has internal impacts. If the change, like a modification of the shared interface, impacts an other team inside the company the cost is higher. If this shared interface is used by multiple teams inside the company, the cost increases again. And lastly, if this change impacts people outside the company, the cost is even more high.

That means the cost of change increases with the “distance” between the provided and consumer (inside the team, inside the company, outside the company) and the number of consumers.

The cost of change leads to different ways of taking the decision to actually do this change or not. According to Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s CEO, there are 2 types of decisions. Type 1 are irreversible decisions, it’s impossible to go back, you have to think carefully before taking them. On the opposite type 2 ones are reversible, they don’t cost 0 but you can change your mind very easily and you take no risk doing them.

If the change has impacts only inside a team, that’s a reversible decision make can be taken locally inside the team. On the opposite, a decision impacting a public facing API provided to people outside the company is an irreversible decision which requires more discussion and a formal approval.Getting the balance right regarding those decisions is key to having an organization that thrives from team autonomy.

Tip #3: Catch accidental breakages

Even when having found the right balance for decision making, people can still do mistakes like replacing a property by another in an API response (that’s actually removing the original property). Such modification breaks the consumers.

That’s why it is important to have separate models (as already said in tip #1). Doing such modification requires more work and requires explicit changes that requires you to think about it and so you’ll notice it.

But you can’t rely only on people actually noticing that, you need testing. And to do tests, you need schema (JSON schema, Protobuf, OpenAPI, …) to actually check the difference between old and new version (that’s also why design first is important).

Tip #4: Expose multiple endpoints

Once you know you are doing a change impacting others, avoid lock step release. Requireing coordination between consumer and provider is the enemy, the anti-thesis of independen deployability. That means, you must give to to consumer to upgrade/

To do so you can expose multiple separates ervice versions. But there are a few challenges doing so:

- Service discovery

- Doubling infrastructure costs money

- Keeping data consistency between the 2 versions can be hard

- And also bug fixing can be bothering

To solve that you can expose 2 endpoints, one for each version inside the same component. That way, you shift from complex infrastructure issue to a more simpler design/implementation issue.

Switching from one version to another can be as simple as using path, the accept header or a domain.

Microservices Indieservices

During Q&A, Mehdi Medjaoui asked Newman how he felt about miniservices, macroservices, nanoservices and other {whatever size}services. His reaction made me burst out laughing (jump at 31:45 to see it), he looked totally desperate and did a long facepalm.

More seriously, he stated that the name microservice which imply “size” is actually a problem. He want to go back in time and choose another name focusing on the real important aspect: independent deployability.

Medjaoui proposed indieservices and after 2 second Newman said that would be probably better than microservices.

Boundaries

The Next API Strategy: Going Borderless by Ronnie Mitra and Choosing between API gateway and service mesh by Mark Cheshire sessions gave really good insights about how to define and manage the internal and external boundaries or your system and they resonate with what Sam Newman said about microservices.

Boundaries as a provider

Mark Cheshire said that at first making the decision between API Management and Service Mesh looks quite simple.

API Management is used for North-South traffic. North being outside the organization and south being inside. With API Management, there’s an API Gateway (a proxy) that sits between the provider and its consumers. Consumers can access to APIs exposed on that gateway by registering to a developer portal. Those APIs are considered as products.

Service Mesh is used for East-West traffic, both sides being inside the organization. Service mesh comes as a side car proxy on microservices which handles the communication with other microservices (dealing with discovery, logs/observability, retry, …).

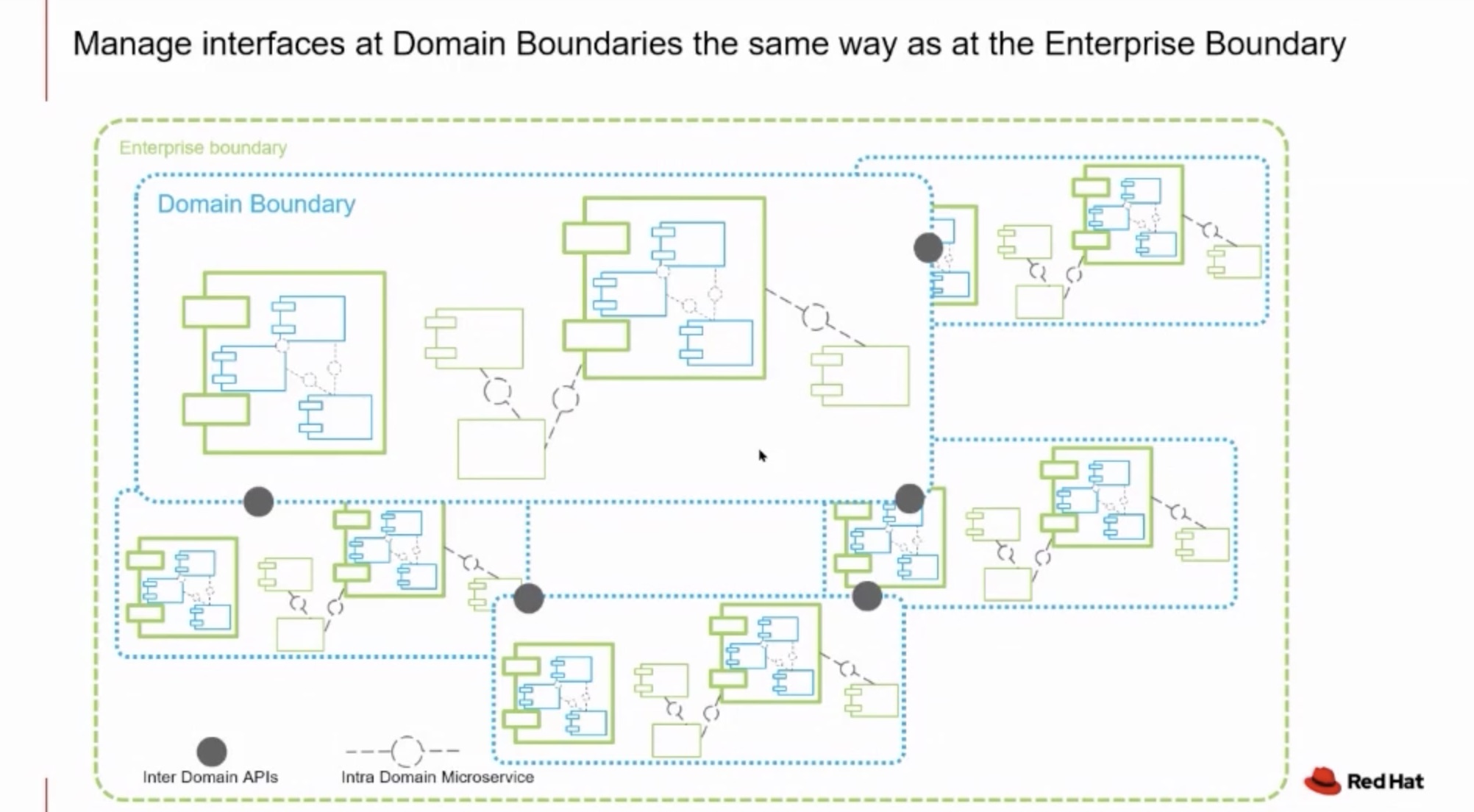

So it looks like the decision should be made on does the communication take place inside or outide my company. But that’s not the case. A company/organization can be split in various domains (however you call them). And these domain boundaries must be treated the same way as enterprise boundary (API Management). Inside the domains you may use service meshes.

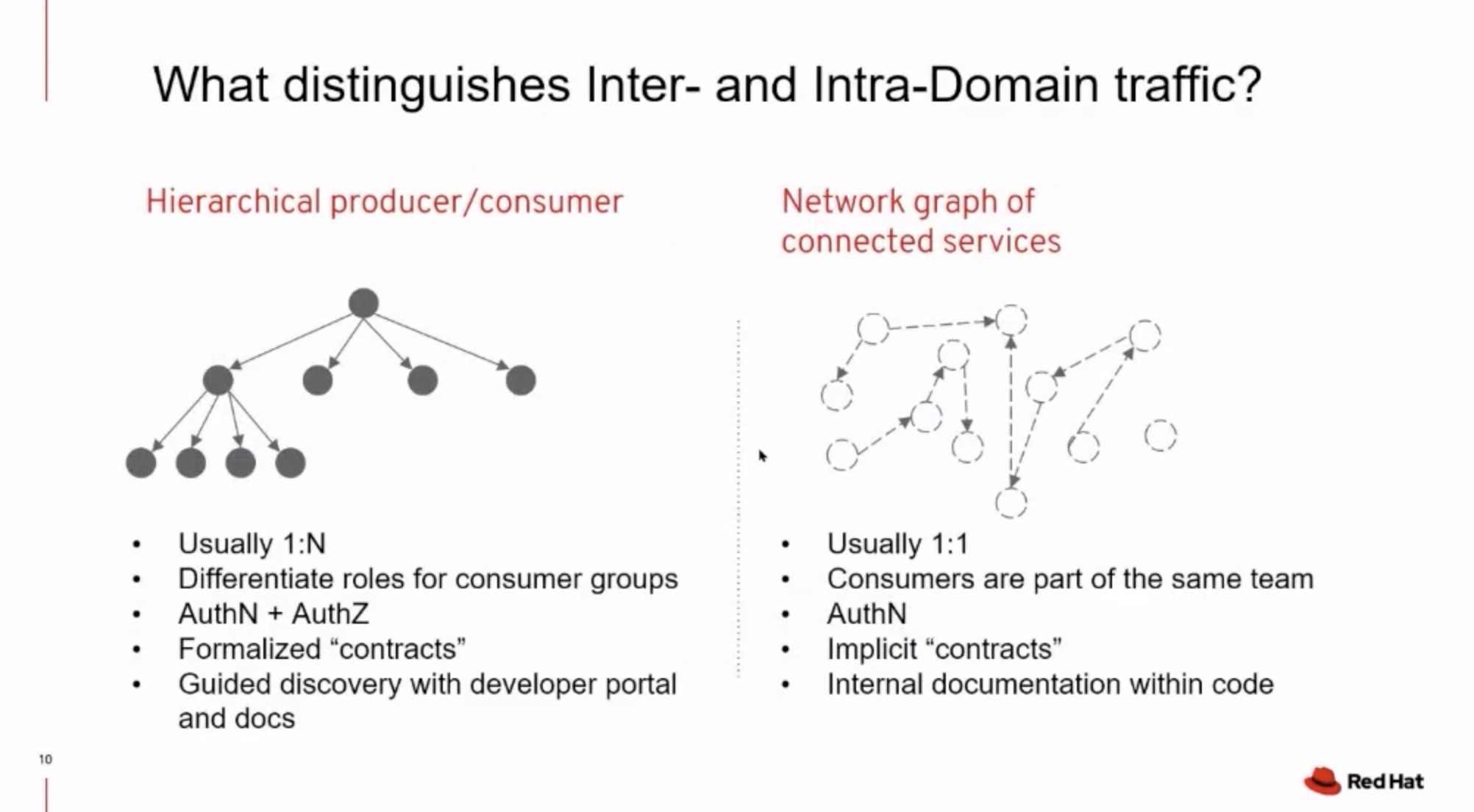

What distingues inter and intra-domain traficc is the relation between provider and consumers. Are they in the same team? How many consumers? Explicit contract needed?

Boundaries as a consumer

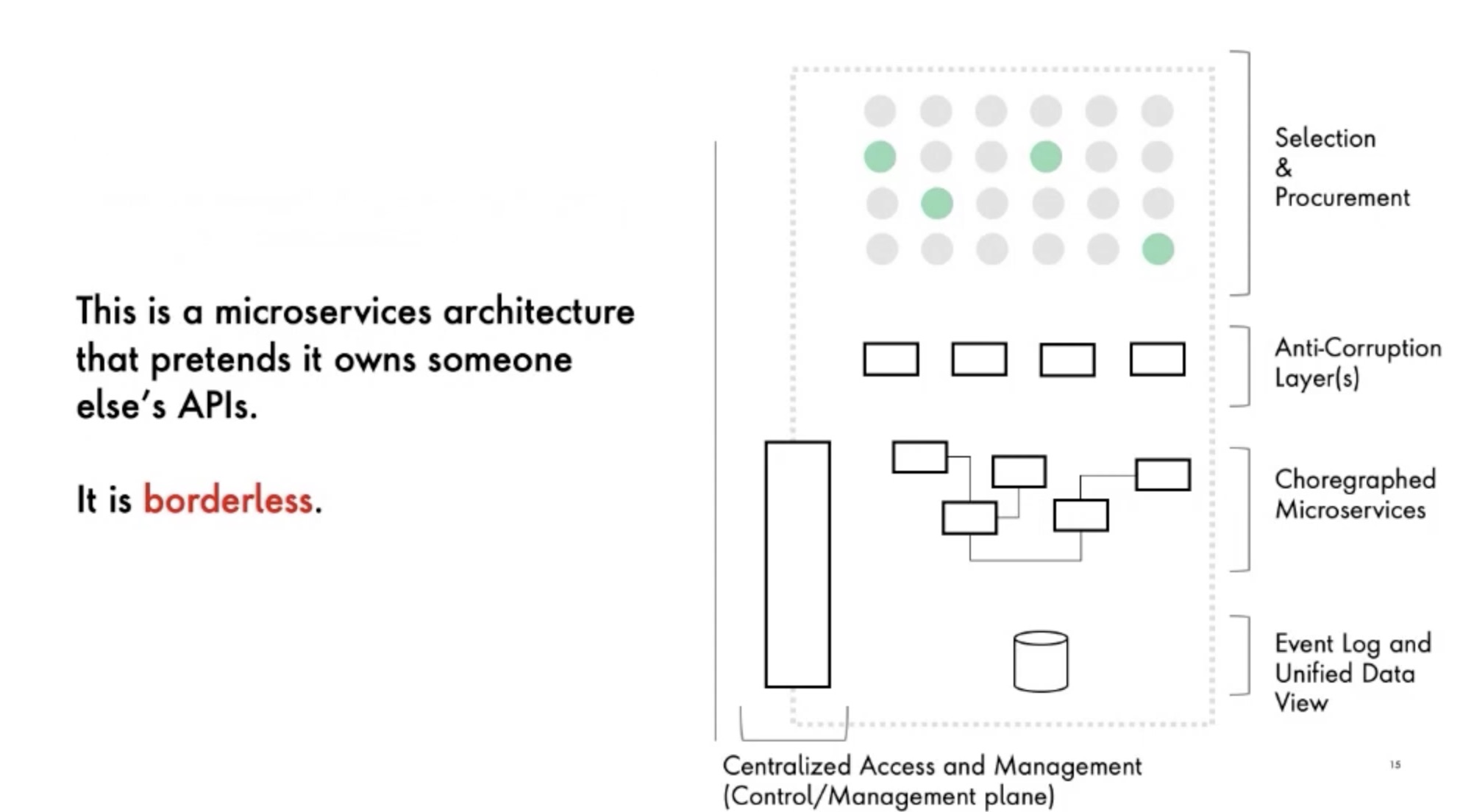

Ronnie Mitra explained that a system is usually complex and difficult to understand and use. Hiding complexity of microservices, APIs, data and third party providers will ease the use of this complex system.

You can’t change someone else’s API (I add: you can’t change someone else’s API even if they are in the same company as yours, but that’s another story I’ll tell another day). In order to avoid building a brittle and tightly couple relation with API providers, you must proxy others APIs with a sub-domain having its own (anti-corruption) model. Reminder: That’s basically what you would do for your own API, separating data/object/API model as sais Sam Newman and Mike Amundsen.

Capabilities don’t interoperate. You may need to build an layer of orchestration to weave microservices capabilities together. There’s a big centralization/decentralization trade-off decision to do here.

Data is all over the place (especially when splitted across dozens if not hundreds of microservices). Data need to be collected and catalgues to be useful.

So many APIs and so many components lead to a system that is difficult to understand and manage. You need to build access and management components that represent this system as a monolith.

By building all these layers, creating new boundaries, you can create a system so simple that it looks totally borderless.

Organization

As you may have noticed, architecture is more about principles and choosing the right organization than technology. Actually technology questions are not the main ones. In his session “APIs are Arrangements of Power. Now what?”, Matthew Reinbold gave really good insights about how organization matters for architecture and strategy.

The most important one is that you can take advantage of architecture to change your organization. This strategy is called the inverse Conway maneuver in reference to Conway’s law that tells “Organizations design systems that mirrors their own communication structure”.

Why doing that? Because in order to succeed, an organization must realigned itself around capabilities and the architecture must be aligned on this too. Changing organization is always hard and sometimes it may be easier to start with architecture, so the inverse Conway maneuver makes sense. And if you don’t think this works, just take a look at what Amazon became after the Jeff Bezos mandates.

Governance

You may want to skip that section because you think governance sucks, but please read it. Indeed, for many people, governance is a dirty word, synonym of pointless, useless and terrible processes and constraints dictated by some crazy people from the top of their ivory towers. And they are right because unfortunately such totally wrong governance exists. Hopefully it’s not always the case, there are some people and company who do governance in a totally different way.

Without proper governance at every level from design to API strategy, your company’s employees will be very sad and your company may even fail. Most sessions were tied in a way or another to governance (even the one I talked about in previous section about architecture). The following ones were explicitely talking about this topic and may give you some ideas to create or improve your existing governance.

| Speaker | Session |

|---|---|

| Alan Glickenhouse, API Strategist @IBM | Recommendations for API Governance and an API Economy Center of Excellence |

| Phil Sturgeon, Architect @Stoplight | Automating style guides for REST, gRPC, or GraphQL |

| Erik Wilde, Co-Author of “Continuous API Management” | How to Guide your API Program and Platform |

| John Phenix, Chief API Architect @HSBC | Automating API Governance |

| Arnaud Lauret, Author of “The Design of Web APIs” | The Augmented API Design Reviewer |

What follows is a summary of all ideas coming from all sessions around governance.

The right level of governance

Governance is not doing the police. Governance is doing all that can be done to make people do the right thing the right way easily. Whatever this thing is, creating an API product, design an API, securing an API, … A very good governance is the one you don’t actually see.

You don’t need to govern everything just because you need it, governance must have a reason, an objective. You must govern as little as possible, you must govern the minimum need to deliver value and manage risk (the consequences of not doing right).

Guidelines

You cannot govern based of personal preferences that will change from one day to another, from one person to another. You need clearly written rules, you need guidelines. Often reduced to API Design Guidelines, you can (even must) create guidelines for every level: API Strategy, API Program, API Platform, API Product, API Design, architecture, domain definition, …

The first step will be to make people share their practices, then you’ll be able to create your guidelines based on those practices.

Guidelines describe (Erik Wilde):

- Why they exist, which issue they are solving

- What can be done to address this issue

- How to implement the solution

One of the major benefits of having guidelines is ensuring a certain level of consistency. Consistency matters because inconcistency wastes times, especially inconsistent API design which means that ALL consumers will have a lot of work to do (Phil Sturgeon).

Automating API Design Reviews

API Design Guidelines are important, but let’s be honest: most APIs developers will not read the organization’s API manifesto. If they do they won’t remember it. If they do they won’t reread it looking for changes (Phil Sturgeon). So you must automate guidelines controls as much as possible to make their (and reviewer’s) life easier.

Phil Sturgeon, John Phenix and myself talked about API Design review automation using Spectral.

We all agreed on the fact that API design review cannot be completely replace by automation. An API linter will not tell you if the design is actually accurate, if this resource’s name is the good one or if the API is actually the one that is needed. But it simplifies the process massively, removing 80% or rejections before reviewers even look.

Scaling and Shifting API Design Governance

The mosy visible aspect of governance is API design governance. Without it, your API landscape will be a totally inconsistent nightmare that will make loose time to all of your consumers. Therefore you must ensure that API are design properly with API design reviews.

Depending on your context (locations, size, number of APIs), you may use different organization model to do so (John Phenix):

- Centralized: A core expert team do all reviews. This is a consistent but not scalable approach

- Federated: API champions enforce standard locally. This is a scalable but not consistent approach.

- Automated: Designs are automatically reviewed by some magic programs. This is scalable and consistent but is far from comprehensive. Indedd, such program will not tell you if the API is the right one.

- Hybrid: Focus human-power on what cannot be checked automatically.

Whatever approach you have, you’ll notice that in the long run the discussions will shift from “Are we doing APIs right” (meaning conforming to our design guidelines) to “Are we doing the right APIs” (API product vision).

Doing APIs right and doing right APIs

It’s time to conclude. What do I retain in the end? Well, besides Sam Newman doing a facepalm, I will remember that “it’s the people that matter, the people that last, not machines, not technology. Change is not Kubernetes or Service Mesh, change is people” (Matthew Reinbold). And also a clever way to say that they are two sides of doing APIs: “Doing APIs right and doing right APIs” (Alianna Inzana and John Phenix). Based on my experience, I can tell you that helping people doing the APIs right with appropriate governance will help them making right APIs by themselves in the long run.